Fleet Ditch

Pat Rogers, University of South Florida

November 2022

The Fleet was the most important of several lost rivers that flowed through London. The name comes from an Anglo-Saxon word flēot, meaning tidal inlet. It rose in separate headwaters flowing from two ponds across Hampstead Heath, one near what was later called the Vale of Heath and the other in the grounds of Kenwood House. These sources merged lower down, close to the area now known as Camden Town. The river ran southwards, passing by modern landmarks such as King’s Cross, St Pancras and Holborn to reach the Thames on the approximate site of Blackfriars Bridge, built in 1769. In Roman times it thought to have been as much as 600 feet wide at this point, but over the course of centuries various factors conspired to reduce its span, both in length and breadth. The history of the Fleet has been summarised as a decline from a river to a brook, from a brook to a ditch, and from a ditch to a drain. The final stage might be more honestly described as a sewer.

Already by medieval times, there were complaints about the way in which the passage of barges upstream was blocked by a combination of silt and rubbish. Periodic attempts were made to clean the waterway, but these were quickly undone by the presence along the banks of wharves, mills and commercial premises, notably those of butchers who threw offal into its stream, not to mention the waste left by pig-keepers and oyster sellers plying their trade there. From time to time, the authorities found it necessary to remove “houses of office” (privies) from the neighbourhood of the river. The Great Fire of 1666 had the happy effect of destroying the scene of some of the offending activities, but this made little difference to an ongoing sanitation problem. In 1661 an aristocratic landowner bent on speculative development around what became Hatton Garden had been allowed to create a sewer whose contents were dispatched into the Ditch, and this practice continued unchecked when the city was striving to rebuild. Although the whole length of the Fleet was affected, it was natural that the urban area surrounding its last half mile produced most of the trouble.

A brave effort was made by Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke to widen and deepen this stretch from Holborn down to the Thames deeper and broader by creating a canal fifty feet across, straddled by elegant bridges. It was railed in for fear that people would fall into the water. Unfortunately the engineers had to cope with many practical problems, as the river kept silting up as fast it was dredged. Moreover, “the local citizens would not discontinue their practice of dumping rubbish in it.” As Nigel Barton describes, the project ran out of money, with some of its main goals not properly realised: the spacious wharves became thoroughfares, used as coach-parks, storage-places, and rubbish dumps: “In 1733 … the authorities bowed to the inevitable and the canal was arched over down to Fleet Bridge…and the central strip [became] a long arcaded covered market.” This was the Stock Market, moved from its former location in the City so that the new Mansion House could be built. Even this did not get rid of all the nuisances that had long been linked to the Ditch, and in 1766 the rest of the canal was covered over. From now, as the historians Wheatley and Cunningham put it, “the famous Fleet Ditch carried its dead dogs and discharging streams to the Thames underground.” Ultimately the market was closed in 1829 to make room for the construction of Farringdon Street, and most of the river disappeared along its length under many feet of concrete.

The phrase about dead dogs and discharging streams recalls the idiom used by numerous comic poets and authors of journalistic surveys of London life. Often the sewers were compared to their disadvantage with the cloacæ of ancient Rome. In the words of Lemprière’s classical dictionary, these were “large receptacles for the filth of the whole city.… and the building was so strong and so firmly constructed … that though they were continually washed by impetuous torrents, they remained in a perfect state during above 700 years.” Their equivalents in London were neither purpose built nor durably constructed. A noted citizen, Ben Jonson was the earliest writer to seize the opportunity to put these impetuous torrents to satiric ends in his mock epic poem, “On the Famous Voyage” from 1616. This describes how two travellers make their way from Bridewell Dock (representing the putrid lake of Avernus) up the hellish river which is the Fleet Ditch, passing from “Styx, to Acheron: / The ever-boiling flood. Whose banks upon / Your Fleet Lane Furies; and hot cooks do dwell.” Others continued to pursue this Line: Samuel Garth’s Dispensary (1699) has “Nigh where Fleet Ditch descends in Sable Streams / Tosh his Sooty Naiads in the Thames,” while as late as 1761 Arthur Murphy thought it worth addressing an Ode to the Naiads of the Fleet Ditch, even though the naiads by this time would have to look for new waters in which to disport themselves.

Better known are the lines in Swift’s urban pastoral Description of a City Shower (1710), which set out the literary image of the Ditch for generations to come:

Now from all Parts the swelling Kennels [gutters] flow,

And bear their Trophies with them as they go:

Filth of all Hues and Odours seem to tell

What Street they sail’d from, by their Sight and Smell.

They, as each Torrent drives, with rapid Force

From Smithfield, or St. Pulchre’s shape their Course,

And in huge Confluent join at Snow-Hill Ridge,

Fall from the Conduit prone to Holborn-Bridge.

Sweepings from Butchers Stalls, Dung, Guts, and Blood,

Drown’d Puppies, stinking Sprats, all drench’d in Mud,

Dead Cats and Turnip-Tops come tumbling down the Flood.

We do not need to be able to follow the exact course traced here, though it is accurate enough physiographically and hydrographically. Contemporaries would have enjoyed decoding not just classical allusions, but also the local references. St. Sepulchre church was linked to the grisly Tyburn executions, when the Parish Clerk rang a bell outside the cell of a condemned prisoner in nearby Newgate goal on the eve of his execution, and read some improving doggerel a little too late in the day. The Conduit is Lamb’s Conduit, a cistern that was fed by a dam partially blocking a small stream that ran eastwards to join the Fleet about a third of a mile upstream from Holborn Bridge. “Prone” is used here in the archaic sense of descending steeply.

It is self-evident that the interest of the poem goes beyond merely charting the lay of the land. The torrential energy of the verses debouches with a sudden gushing climax into the final triplet. This recreates the scene chiefly with short nouns, verbs and adjectives spat out by the initial plosive consonants (b, c, d, g, p and t).

Soon afterwards John Gay developed the town eclogue that his friend Swift had pioneered with a mock georgic, Trivia: or, the Art of Walking the Streets of London (1716). A central episode in the poem, as augmented in 1720, creates a foundational myth for Cloacina, the presiding deity of the sewers, invoked as “Goddess of the Tide / Whose sable Streams beneath the City glide.” In both Swift and Gay, we find a subterranean text, conveying the idea that the modern world depends on a hidden propulsive force that is set in motion by currents of dirt, as they flow ceaselessly under the feet of residents who are walking its streets. Waste is the lifeblood of urban existence, and here the Ditch has come to be the very guts of London.

It was Pope who made the most extensive use of this theme in the second book of the Dunciad.

Cloacina also figures in this sequence, where she bestows favours on her servant, the purveyor of obscene literature Edmund Curll. He is said to have “fish’d her nether realms for Wit,” close to her “black grottos near the Temple-wall”—that is to say, coal wharves slightly upstream from the Fleet, located not very far from Curll’s business when his shop stood opposite St. Dunstan’s church in Fleet Street. Coals from Newcastle were brought by collier ships up the Thames and, until the river was covered, loaded on to barges that carried them up as far as Holborn: one street parallel to the Ditch was called Seacoal Lane. (This is the joke behind Garth’s use of the phrase “Sooty Naiads.”) From this point, the action of the poem proceeds as the dunces embark on the second stage of their games:

This labour past, by Bridewell all descend,

(As morning-pray’r and flagellation end)

To where Fleet-ditch with disemboguing streams

Rolls the large tribute of dead dogs to Thames,

The King of dykes! than whom no sluice of mud

With deeper sable blots the silver flood.

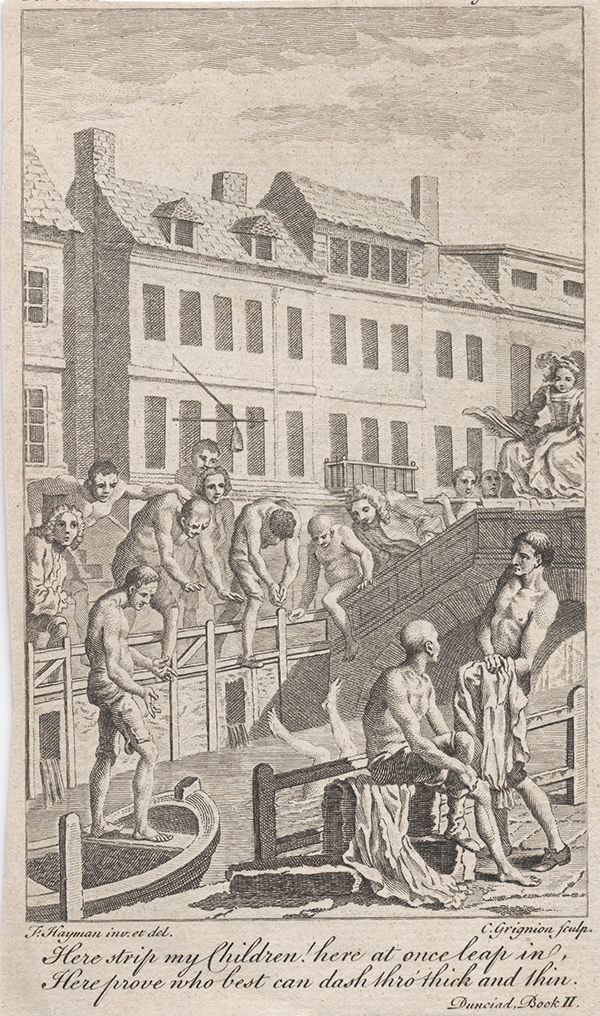

An illustration for this sequence, designed by Francis Hayman, shows the games going forward in the shadow of the Fleet Bridge, with a participant diving from "a stranded lighter" (one of the coal barges that periodically got stuck in the mud). After this, the dunces are able to find refuge in the Fleet prison, where debtors were confined: "While others timely, to the neighbouring Fleet / (Haunt of the Muses) made their safe retreat.”

The prison, partly because of its association with clandestine “Fleet weddings”, was one of the prominent features of the landscape that lined the course of the Ditch, and inevitably affected its reputation. Among these were Bridewell, the house of correction for vagrants and disorderly persons; Whitefriars, the former sanctuary for criminals known as Alsatia; the environs of Smithfield, once the place where heretics were burnt at the stake, by this date a meatmarket bordering on the site of Bartholomew Fair with its annual saturnalia; and Hockley in the Hole, the home of bull- and bear-baiting. All of these came in for their share of criticism, solemn or facetious. None, however, called out more incisive treatment in literature than the muddy waters of the Fleet Ditch.

Plate from The Dunciad, Book II (1751). "Here strip my children! Here at once leap in ..." by Charles Grignion, printmaker (1721–1810). Lewis Walpole Library 751.00.00.27.2. Public Domain. |