Frost Fairs

Pat Rogers, University of South Florida

June 2023

The climate of Northern Europe began a gradual warming trend over the course of the eighteenth century, after the rigours of the preceding ages. Even so, the Little Ice Age that began in the late Medieval period had its coldest cycle between 1680 and 1730, and did not relax its full grip until about 1850. The waters around Britain were at least five degrees cooler than today, and there were many periods of intense cold. The Thames froze over at London quite regularly, up to once a decade on average. Since the replacement of the closely spaced piers of the medieval London Bridge in 1831, a complete freeze is unknown on the tidal river.

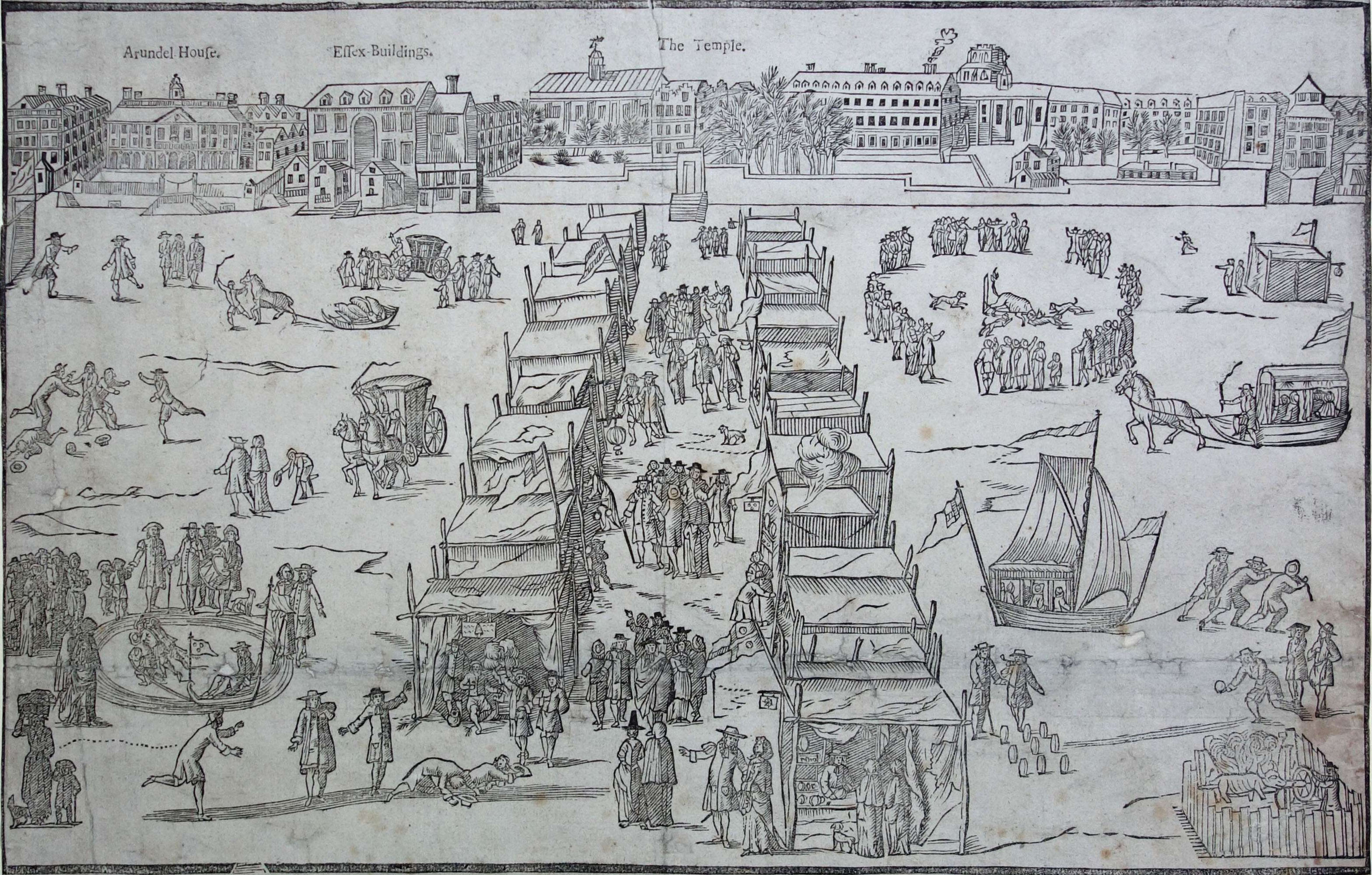

Among the most famous of these extreme winters were those of 1608, 1683–84, 1715, 1739–49, 1789 and 1814, when the traditional frost fair took place. The bitter cold in late 1683 ushered in a particularly severe and prolonged spell, from mid-December to early February, with ice on the Thames to an estimated depth of up to one foot (30.5 cm). The fair lasted for several weeks and included a large amount of commercial activity together with a variety of entertainments such as bull-baiting and other “shows and tricks.” John Evelyn wrote a graphic description of the occasion:

The frost continues more and more severe, the Thames before London was still planted with booths in formal streets, all sorts of trades and shops furnished, and full of commodities, even to a printing press, where the people and ladies took a fancy to have their names printed, and the day and year set down when printed on the Thames: this humor took so universally, that it was estimated that the printer gained £5 a day, for printing a line only, at sixpence a name, besides what he got by ballads, etc.

Coaches plied from Westminster to the Temple, and from several other staires to and fro, as in the streetes, sliding with skeetes, a bull-baiting, horse and coach races, puppet plays and interludes, cookes, tipling and other lewd places, so that it seemed a bacchanalian triumph or carnival on the water, whilst it was a severe judgement on the land, the trees not onely splitting as if lightning-struck, but men and cattle perishing in divers[e] places, and the very seas so lock’d up with ice, that no vessels could stir out or come in.”

An ox was roasted opposite the entrance to Whitehall (close to where Westminster Bridge would be built in the 1740s), and a portion was allegedly consumed by Charles II.

The end of the year 1715 and early weeks of 1716 saw another long spell of freezing weather and another fair on the river. This is how the scene was depicted in a newsletter sent out from London into the provinces:

The Thames seems now a solid rock of ice; and booths for the sale of brandy, wine, ale, and other exhilarating liquors, have been for some time fixed thereon; but now it is in a manner like a town: thousands of people cross it, and with wonder view the mountainous heaps of water, that now lie congealed into ice. On Thursday, a great cook’s-shop was erected, and gentlemen went as frequently to dine there, as at any ordinary. Over against Westminster, Whitehall, and Whitefriars, Printing-presses are kept upon the ice, where many persons have their names printed, to transmit the wonders of the season to posterity.

Among those who ventured out to test the conditions on 17 January were the Prince of Wales and the ageing Duke of Marlborough, when they, “with several other Noblemen, went on the Thames on the Ice, from Old Palace Yard to Lambeth, and back again; through the loud Hazzas and Acclamations of the People”. This must be one of the few occasions when a frozen river provided the backdrop to a party political spectacle. In the preceding weeks, the Jacobite prisoners captured at the battle of Preston had been carted down to London through the chilly country roads. The show trial of six lords who had taken some part in mounting the Rising took place on 19 January. All received a sentence of death. One escaped and two were reprieved, ultimately gaining release without a pardon. But two were beheaded at Tower Hill on 24 February. Justice in those days, though often denied, was seldom delayed. By that time, the frost had begun to melt and there was no longer a need for the distractions of a fair.

The ”Great Frost” of 1739–40 started around Christmas Day once more, and again it lasted into the third week of February. It followed some milder winters in the previous decade. A few days after its arrival, a huge blizzard struck the Thames estuary, creating a landscape of icebergs and floes that gave the river a strangely Arctic appearance. Many ships, large and small, at anchor or at sea, were destroyed. Even after a thaw came, the weather remained unusually cold throughout the year, which had multiple side-effects, including disastrous harvests and a major food crisis with widespread deaths among the poor. The situation was worst in Ireland, where the grain and potato crops failed, and led to the first instance of “climate migration,” anticipating the famine conditions of a century later. While England fared better, the capital itself suffered as inhabitants endured their share of what has been termed “the longest period of extreme cold in modern European history.” Unsurprisingly, Londoners took such advantage as they could of the situation, stoically erecting shops and booths to enjoy either retail therapy or popular entertainments such as puppet shows and acrobats. For a few weeks, it was as though Bartholomew Fair had been transported from Smithfield to the ice-covered waters of the Thames.

Fairs were held on three more occasions, in 1767–68, 1788–89, and 1812, but they were of shorter duration. Again, the traditional festivities were held against the background of a shortage of food, fuel and water, producing a spike in the mortality rate among the poorest classes. Victorian London had to deal with many environmental hazards caused by natural disasters, as well as disease and overcrowding, but the residents were at least spared the prolonged spells of freezing weather that their forebears had to expect every few years.

Frost Fair, 1683. View from the frozen Thames toward the Temple and Essex and Arundel Houses (1684). British Museum 1931,1114.361. © The Trustees of the British Museum. This image is provided under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. In certain other jurisdictions it is considered to be in the public domain. (Note: this image has been straightened.–Ed.) |

Frost Fair on the Thames, 1683. Yale Center for British Art B1976.7.113. (Note: this image has been colour corrected.–Ed.) |