George Lyttelton 1st Baron Lyttelton (1709–1773)

Identifiers

- Grubstreet: 193

- Wikidata: Q336899

Names

- George Lyttelton 1st Baron Lyttelton

- George Lyttelton Lord Lyttelton

- Sir George Lyttelton 5th Baronet

- George Littleton

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

LYTTELTON, GEORGE, first Baron Lyttelton (1709–1773), born on 17 Jan. 1709, was the eldest son of Sir Thomas Lyttelton, bart., of Hagley, Worcestershire, by his wife Christian, second daughter of Sir Richard Temple, bart., of Stowe, Buckinghamshire, and sister of Richard, first viscount Cobham. He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, where he matriculated on 11 Feb. 1726, but did not take any degree. He was distinguished as a scholar both at school and at the university. His tutor at Oxford was Francis Ayscough [q. v.], who subsequently married his sister Ann. Early in 1728 Lyttelton set out for the usual grand tour on the continent, returning to England towards the close of 1731. He was at Soissons during the meeting of the congress, and from Rome wrote the poetical epistle to Pope which is prefixed to many of the editions of Pope's ‘Works.’ Lyttelton's letters written during this tour to his father are printed in his ‘Works’ (iii. 209–303). Soon after his return to England he joined in the opposition to Walpole, and was appointed equerry to the Prince of Wales, whose ‘chief favourite’ he quickly became (Memoirs, i. 51). In 1730 he wrote ‘Observations on the Reign and Character of Queen Elizabeth,’ which still remains in manuscript. At a by-election in March 1735 he was returned to the House of Commons for Okehampton, Devonshire, a borough which he continued to represent until his elevation to the House of Lords. He made his maiden speech in the House of Commons on 29 April 1736 upon the congratulatory address on the marriage of the Prince of Wales (Parl. Hist. ix. 1223–5). Though he had urged the prince, in an able letter dated 12 Oct. 1735, not to ask for an increased allowance (Memoirs, i. 74–8), he both spoke and voted for Pulteney's motion on 22 Feb. 1737, and in August of that year was appointed the prince's secretary in the place of Pelham (Works, iii. 312). In this year he contributed two papers to ‘Common Sense, or the Englishman's Journal’ (9 April and 15 Oct.), and is said to have previously written some articles for the ‘Craftsman.’ On 3 Feb. 1738 he spoke in favour of Shippen's amendment for the reduction of the army (Parl. Hist. x. 405–17). The government writers abused him for his opposition to Walpole, and were answered by Chesterfield in ‘Common Sense’ for 4 March 1738 (Chesterfield, Works, 1853, v. 204–8). In February 1739 Lyttelton attacked the convention with Spain, and again urged the reduction of the standing army (Parl. Hist. xi. 956–60, 1283–90). On 29 Jan. 1740 he supported Sandys's Place Bill in an able speech (ib. xii. 335–9), and on 21 Feb. following spoke in favour of Pulteney's motion for an inquiry into the conduct of the authors and advisers of the convention with Spain (ib. xi. 506–9). In February 1741 he both spoke and voted for Sandys's motion for the dismissal of Walpole (ib. xi. 1370–2), and at the general election in May of that year unsuccessfully contested Worcestershire. About this time he is said by Richard Glover [q. v.] to have tried to come to terms with Walpole (Memoirs by a Celebrated … Character, 1814, pp. 4–5). In March 1742 he spoke in favour of the inquiry ‘into the conduct of our affairs both at home and abroad during the last twenty years,’ as well as for the resolution for the appointment of a committee to inquire into Walpole's conduct (Parl. Hist. xii. 517–22, 584–6). After the death of Wilmington, Lyttelton favoured a coalition with Pelham for the overthrow of Carteret, and formed one of the committee of nine to whom the direction of the opposition policy was entrusted. Upon Carteret's downfall Lyttelton was appointed a lord of the treasury in the Broad Bottom administration (25 Dec. 1744), and was immediately dismissed from his post in the household of the Prince of Wales. In April 1747 he distinguished himself in the debate on the second reading of the bill for taking away the heritable jurisdictions in Scotland, and ‘made the finest oration imaginable’ (Works, iii. 3–17; Walpole, Letters, ii. 81). In 1749 he refused Pelham's offer of the treasurership of the navy in favour of his friend Henry Bilson-Legge [q. v.] In January 1751 he voted with Pitt against Pelham's motion for the reduction of the seamen (Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of George II, i. 12–13), and in March following delivered an elaborate set speech in favour of the Mutiny Bill (Works, iii. 18–29). Shortly before the Prince of Wales's death in this month Lyttelton appears to have made some attempts to conciliate his old master, which, according to Walpole, explained the secret of his ‘oblique behaviour this session in parliament’ (Memoirs of the Reign of George II, i. 201–2). On the death of his father in September 1751 Lyttelton succeeded to the baronetcy and the family estates. In November 1753 he supported the repeal of the Jews' Naturalisation Bill, which had been passed in the preceding year (Works, iii. 30–6). On Pelham's death Lyttelton resigned his seat at the treasury board, and, having accepted the post of cofferer in the Duke of Newcastle's administration (April 1754), was admitted a member of the privy council on 21 June 1754. His refusal to join Pitt in opposing the Duke of Newcastle led to the severance of their ‘historic friendship’ (Memoirs, ii. 477–81, 489–491), and on 29 Nov. 1756, after Lyttelton's unsuccessful attempt to conciliate the Duke of Bedford, the breach was openly avowed by Pitt. Instead of resigning when his friends were turned out, Lyttelton accepted the post of chancellor of the exchequer in the place of Bilson-Legge (22 Nov. 1755), an appointment ‘which was resented with the greatest acrimony by the whole of the cousinhood’ (Lord Waldegrave, Memoirs, p. 58), and occasioned Horace Walpole to remark that ‘they turned an absent poet to the management of the revenue, and employed a man as visionary as Don Quixote to combat Demosthenes’ (Memoirs of the Reign of George II, ii. 63). On 23 Jan. 1756 Lyttelton opened the budget ‘well enough in general, but was strangely bewildered in the figures.’ Pitt's attack on his proposal to mortgage the sinking fund led to a debate which was ‘entertaining enough, but ended in high compliments’ (Walpole, Letters, ii. 500). On the 25th of the following month Lyttelton introduced his plan of supplies and taxes for the current year. His speech on this occasion must have been somewhat wanting in lucidity, as ‘he never knew prices from duties nor drawbacks from premiums’ (ib. ii. 511). On 11 May Lyttelton moved for a vote of credit for a million, which led to an altercation between him and Pitt, who insisted on knowing for what the money was designed. The Duke of Newcastle reported to the king that Lyttelton showed the ‘judgment of a minister, the force and wit of an orator, and the spirit of a gentleman’ (Memoirs, ii. 525). On the resignation of the Duke of Newcastle in November Lyttelton retired from office, and on 18 Nov. 1756 was created Baron Lyttelton of Frankley in the county of Worcester. He took his seat in the House of Lords on 2 Dec. following (Lords' Journals, xxix. 6), and spoke for the first time in the discussion of the Militia Bill, when he ‘had a sparring’ with Lord Talbot (Memoirs, ii. 602). During the debates on the Prussian treaty and on the bill for the extension of the Habeas Corpus Act in 1758, Lyttelton was violently attacked by Temple, and on the latter occasion both peers were compelled by the house to promise that the matter should go no further (Lords' Journals, xxix. 347). He opposed the Cider Bill in 1763, and spoke so well against it on the second and third readings as to extort the praise of Horace Walpole. His speech on 29 Nov. 1763, in support of the motion against the extension of the privilege of parliament to the writing and printing of seditious libels, is the only one which is preserved of this debate in the House of Lords (Works, iii. 37–47). On 21 Feb. 1764 he moved a resolution censuring Brecknock's ‘Droit le Roi,’ which was carried, and the book was ordered to be burnt (Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of George III, i. 384). In this year Lyttelton, who had lately become reconciled with Pitt and Temple, endeavoured to effect a reconciliation between them and Grenville with a view to forming a party against Bute. On 30 April 1765 he took part in the debate on the second reading of the Regency Bill, insisting that the regent should be nominated by the king in conjunction with parliament; but on 1 May his motion ‘urging that the crown cannot devolve its power on unknown persons’ was rejected by 89 to 31 votes (Walpole, Reign of George III, ii. 116–19; see Memoirs, ii. 665–675). During the prolonged attempt at the promotion of a new administration Lyttelton refused the offer of the treasury which was made to him by the Duke of Cumberland (May 1765). He did his best, however, to bring the negotiations between Pitt and Temple to a successful issue. On the formation of Rockingham's first administration in July 1765 Lyttelton refused a seat in the cabinet, and again declined to separate himself from Pitt and Temple. On 17 Dec. 1765 he supported the amendment to the address, and advocated the adoption of stronger measures against the American colonists. In a long and elaborate speech he opposed the repeal of the Stamp Act in January 1766 (Memoirs, ii. 692–703), and signed both the protests against the bill, the first of which was drawn up by himself (Rogers, Protests of the Lords, 1875, ii. 76–89). In December 1766 he took part in the debate on the Indemnity Bill. A pamphlet entitled ‘A Speech in behalf of the Constitution against the suspending and dispensing Prerogative, &c.,’ sometimes attributed to Grenville, but said to have been written by one Macintosh with the assistance of Lyttelton and Temple, preserves the arguments, and has been reprinted in the ‘Parliamentary History’ (xvi. 251–313). In the expectation that Chatham was about to resign, Lyttelton in March 1767 sent George Grenville ‘a project of a ministry to be formed … by a coalition of the Grenvillians with the Rockinghams and Bedfords,’ in which he assigned himself the place of ‘cabinet councillor extraordinary’ without office (Grenville Papers, iv. 8; see also Lord Albemarle, Memoirs of the Marquis of Rockingham, ii. 30–2). In the same month he took part in the debate on the bill for giving an income of 8,000l. to the royal dukes, and objected at length to the manner in which the provision was to be made (Memoirs, ii. 713–720). On 2 Feb. 1770 he spoke in favour of Rockingham's resolution condemning the proceedings of the House of Commons against Wilkes (ib. pp. 756–8), and in 1772 strongly discountenanced the idea of the secession of the whig party from the house. He died at Hagley on 22 Aug. 1773, aged 64, and was buried in the parish church, where an inscription to his memory was cut by his desire on the monument erected by him to his first wife.

Lyttelton was descended from William, the eldest son of Sir Thomas Littleton [q. v.], author of the ‘Treatise on Tenures,’ and upon his father's death inherited the Hagley property, which had been in the possession of the family since 1564. His powerful political connection was the chief cause of his importance in parliament. Through the marriage of his maternal aunt, Hester Temple (afterwards Countess Temple), with Richard Grenville of Wootton, Buckinghamshire, Lyttelton was first cousin to Richard Temple Grenville, earl Temple [q. v.], and to George Grenville [q. v.]; while by the marriage of his sister Christian with Thomas Pitt of Boconnoc, Cornwall, he became connected with William Pitt, who in 1754 married Lyttelton's first cousin, Hester Grenville. With Pitt and the Grenvilles Lyttelton formed the small but powerful party which was known until the death of his maternal uncle, Lord Cobham, in 1749, as the ‘Cobhamites,’ and subsequently as ‘the Grenville cousins’ or ‘the cousinhood.’

Lyttelton, who is known as ‘the good Lord Lyttelton,’ was an amiable, absent-minded man, of unimpeachable integrity and benevolent character, with strong religious convictions and respectable talents. In spite of his ‘great abilities for set debates and solemn questions’ (Chatham Correspondence, i. 106), his ignorance of the world and his unreadiness in debate made him a poor practical politician. In appearance he was thin and lanky, with a meagre face and an awkward carriage, but ‘as disagreeable as his figure was, his voice was still more so, and his address more disagreeable than either’ (Lord Hervey, Memoirs, 1884, ii. 99). Lord Chesterfield draws an amusing picture of Lyttelton's ‘distinguished inattention and awkwardness,’ which he holds up as a terrible warning to his son (Letters and Works of the Earl of Chesterfield, i. 316–17). As an author Lyttelton had at one time a considerable reputation. He was painstaking and industrious, but never original. The most important of his prose works were: 1. ‘Letters from a Persian in England to his friend at Ispahan,’ 1735. 2. ‘Observations on the Conversion and Apostleship of St. Paul,’ 1747. 3. ‘Dialogues of the Dead,’ 1760. 4. ‘The History of the Life of Henry the Second,’ &c., 1767–71. The best of his poetical pieces is the ‘Monody’ to the memory of his wife, 1747. Among his numerous correspondents, whose letters are preserved at Hagley, were Bolingbroke, Chesterfield, Doddridge, George Grenville, Marchmont, Pitt, Pope, Admiral Rodney, Thomson, Voltaire, and Warburton. Bolingbroke originally wrote his ‘Idea of a Patriot King’ in the form of a letter to Lyttelton, who declined the honour (14 April 1748) on account of his close connection with many of Walpole's best friends (Memoirs, ii. 428). Lyttelton was a liberal patron of literature. His friendship with Pope, who refers to him in the ‘First Epistle of the First Book of Horace’ (line 30),

Still true to virtue, and as warm as true,

formed the subject of an attack upon him in the House of Commons by Fox in 1740 (Memoirs, i. 115–16). He befriended Thomson, who describes his patron in the ‘Castle of Indolence’ (canto i. stanzas 65 and 66), and whose own description in the same poem was written by Lyttelton (ib. stanza 68). Through his influence Thomson's posthumous tragedy, ‘Coriolanus,’ was acted in January 1749 at Covent Garden Theatre for the benefit of Thomson's family. Quin spoke the prologue, which was written by Lyttelton, and contains the oft-quoted lines (Works, iii. 199):

Not one immoral, one corrupted thought,

One line which, dying, he could wish to blot.

An edition of the ‘Works of James Thomson’ was published under Lyttelton's superintendence in 1750 (London, 12mo, 4 vols.). In this edition Lyttelton made many corrections, cutting down the five parts of ‘Liberty’ into three. From an interleaved copy at Hagley it appears that Lyttelton intended to make considerable alterations in the ‘Seasons.’ A manuscript copy of them will be found in a volume of Thomson's ‘Works’ (1768) now in the British Museum. He assisted his old schoolfellow, Henry Fielding, who in return dedicated ‘Tom Jones’ to him in 1749, and declared (preface) that the name of his patron would be a sufficient guarantee for his decency. Lyttelton also helped Edward Moore in the establishment of the ‘World’ (1753–6). He procured for Archibald Bower [q. v.] the keepership of Queen Caroline's library, and appointed Joseph Warton his domestic chaplain. Other literary friends were Glover, James Hammond, and Shenstone, who placed an inscription to him at the Leasowes. Horace Walpole seldom lost an opportunity of sneering at Lyttelton, and Lord Hervey evidently did not appreciate him. Smollett, besides writing an unfeeling burlesque of Lyttelton's ‘Monody,’ made offensive allusions to him in ‘Roderick Random’ and ‘Peregrine Pickle’ (where Lyttelton is caricatured as Gosling Scragg), for which, however, he subsequently apologised. Johnson's dislike to Lyttelton, which shows itself in the ‘Lives of the Poets,’ has been attributed to their rivalry for the good graces of Miss Hill Boothby [q. v.] (Autobiography of Mrs. Piozzi, 1861, i. 32–4). The character of ‘a respectable Hottentot’ in Chesterfield's ‘Letters’ was probably intended for Lyttelton.

Lyttelton rebuilt Hagley, 1759–60, with the assistance of Saunderson Miller of Radway, Warwickshire, an amateur architect (Harris, Life of Lord Hardwicke, ii. 456–7). The beauties of the place have been described in Thomson's ‘Spring’ (The Seasons, 1744, lines 900–58), Dr. Pococke's ‘Travels’ (i. 223–30, ii. 233–6, Camd. Soc.), and Horace Walpole's ‘Letters’ (ii. 352). The ‘very affecting and instructive account’ of Lyttelton's last illness and death, quoted by Johnson in his ‘Life of Lyttelton,’ was written by Lyttelton's physician, Dr. Johnstone of Kidderminster, to Mrs. Montagu, and printed in ‘Gent. Mag.’ for December 1773 (xliii. 604).

Lyttelton married first, in June 1742, Lucy, daughter of Hugh Fortescue of Filleigh, Devonshire, and his second wife, Lucy, daughter of Matthew, first baron Aylmer, by whom he had one son, Thomas, who succeeded him as second baron Lyttelton [q. v.], and two daughters, viz. Mary, who died an infant, and Lucy, who married, on 10 May 1767, Arthur, viscount Valentia, afterwards first earl of Mountmorris, and died leaving issue in 1783. Lyttelton's first wife died on 19 Jan. 1747, aged 29, and was buried at Over Arley, Staffordshire. He married secondly, on 10 Aug. 1749, Elizabeth, daughter of Field-marshal Sir Robert Rich, bart. [q. v.] Unlike the first, the second marriage was unhappy, and they subsequently separated. Lady Lyttelton survived her husband many years, and died on 17 Sept. 1795.

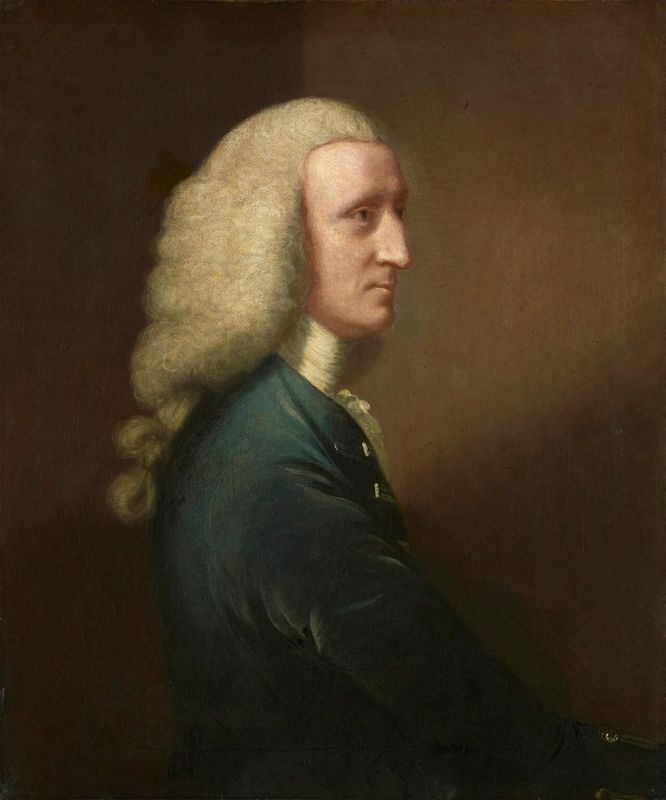

Portraits of Lyttelton and his first wife, by Sir Joshua Reynolds and John M. Williams respectively, were exhibited at the Loan Collection of National Portraits at South Kensington in 1867 (Cat. Nos. 338, 335). A portrait of Lyttelton by an unknown painter is in the National Portrait Gallery. He appears in the celebrated caricature called ‘The Motion,’ which was published in February 1741 (Cat. of Prints and Drawings in the Brit. Mus. vol. iii. pt. i. pp. 369–72), and there are engravings by Dunkarton and others after a fourth portrait by Benjamin West.

Lyttelton was author of: 1. ‘Blenheim,’ a poem on the Duke of Marlborough's seat, London, 1728, fol., anon. 2. ‘An Epistle to Mr. Pope, from a young gentleman at Rome,’ London, 1730, 8vo, anon. 3. ‘The Progress of Love,’ in four eclogues, London, 1732, fol., anon.; London, 1732, fol. The first of these eclogues was dedicated to Pope, by whom they were corrected for the press. They ‘cant,’ says Johnson, ‘of shepherds and flocks, and crooks dressed with flowers’ (Johnson, Works, xi. 380). 4. ‘Advice to a Lady,’ a poem, London, 1733, fol., anon. 5. ‘Observations on the Life of Cicero,’ London, 1733, 8vo, anon.; 2nd edit. London, 1741, 8vo, anon. 6. ‘Letters from a Persian in England to his friend at Ispahan,’ London, 1735, 8vo; 5th edit. 1774, 12mo. Printed in the first volume of Harrison's ‘British Classicks’ in 1787 and 1793, London, 8vo. Four of these letters which appear in the earlier editions are omitted in the third edition of Lyttelton's ‘Miscellaneous Works.’ 7. ‘Considerations upon the Present State of our Affairs at Home and Abroad, in a Letter to a Member of Parliament from a Friend in the Country,’ London, 1739, 8vo; 2nd edit. London, 1739, 8vo. 8. ‘To the Memory of a Lady [Lucy Lyttelton] lately deceased: a Monody,’ London, 1747, fol., anon.; 2nd edit. London, 1748, fol. 9. ‘Observations on the Conversion and Apostleship of St. Paul. In a Letter to Gilbert West, Esq.,’ London, 1747, 8vo, anon.; 9th edit. London, 1799, 8vo; a new edition, London, 1799, 12mo; other editions, Edinburgh, 1812, 12mo; Edinburgh, 1821, 12mo; London [1868], 8vo; London [1879], 8vo. It was frequently attached to Gilbert West's ‘Observations on the History and Evidences of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ,’ and was translated into French by l'Abbé Guénée, 1754, 12mo; by Jean Deschamps, 2nd edit. 1758, 12mo. According to Johnson, ‘infidelity has never been able to fabricate a specious answer’ to this treatise. 10. ‘Dialogues of the Dead,’ London, 1760, 8vo, anon.; 2nd edit. London, 1760, 8vo; 3rd edit. London, 1760, 8vo; 4th edit., corrected, to which are added four new dialogues, London, 1765, 8vo. Reprinted in Harrison's ‘British Classicks,’ vol. vii. London, 1795, 8vo. First American edition from the fifth London edition, corrected, Worcester, Mass., 1797, 12mo. Reprinted in Cassell's ‘National Library,’ No. 190, London, 1889, 8vo. Translated into French by Élie de Joncourt and by Jean Deschamps. Three of these dialogues, viz. Nos. 26, 27, and 28, were written by Mrs. Montagu. 11. ‘Four new Dialogues of the Dead,’ London, 1765, 8vo, anon. 12. ‘The History of the Life of Henry the Second, and of the Age in which he lived, in five books: to which is prefixed a History of the Revolutions of England from the Death of Edward the Confessor to the Birth of Henry the Second,’ London, 1767, 4to, 3 vols., viz. vols. i. and ii., and an unnumbered volume entitled ‘Notes to the Second and Third Books of the History of the Life of King Henry the Second, with an Appendix to each;’ 2nd edit. London, 1767, 4to; 3rd edit. London, 1769, 8vo, 4 vols. Vol. iii. London, 1771, 4to; 2nd edit. London, 1772–3, 8vo, 2 vols. This heavy but conscientious piece of work was the labour of the greater part of Lyttelton's life. Johnson says that ‘the whole book was printed twice over, and a great part of it three times, and many sheets four or five times,’ and that this ‘ambitious accuracy’ cost Lyttelton at least 1,000l. His statement that three volumes were published in 1764 would appear to be incorrect. It was announced as ‘this day published’ in the London ‘Evening Post’ for 16 July 1767, and was first reviewed in the ‘Critical Review’ for July 1767, and in the ‘Monthly Review’ for August 1768. Alluding to this book, on 31 July 1767 Horace Walpole cruelly remarks: ‘How dull one may be, if one will but take pains for six or seven and twenty years together’ (Letters, v. 58). 13. ‘An Account of a Journey into Wales, by George, Lord Lyttelton,’ appended to ‘A Gentleman's Tour through Monmouthshire and Wales,’ &c., London, 1781, 8vo.

The following have been ascribed to Lyttelton, but are not included in the third edition of his ‘Works:’ 1. ‘Farther Considerations on the Present State of Affairs … with an Appendix; containing a True State of the South Sea Company's Affairs in 1718,’ London, 1739, 8vo, anon.; 2nd edit. (with a somewhat different title) London, 1739, 8vo. 2. ‘The Court-Secret: a Melancholy Truth, now first translated from the original Arabic by an Adept in the Oriental Tongues,’ London, 1742, 8vo, anon. 3. ‘The Affecting Case of the Queen of Hungary in relation to both Friends and Foes: a fair Specimen of Modern History, by the Author of “The Court-Secret,”’ London, 1742, 8vo. 4. ‘A Letter to the Tories,’ London, 1747, 8vo; 2nd edit. London, 1748, 8vo. This pamphlet is signed ‘J. H., June 9, 1747.’ In reply Horace Walpole wrote anonymously ‘A Letter to the Whigs, occasion'd by the Letter to the Tories’ (London, 1747, 8vo), and ‘A Second and Third Letter to the Whigs, by the Author of the First’ (London, 1748, 8vo), while Edward Moore defended Lyttelton from Walpole's attack in ‘The Trial of Selim the Persian for divers High Crimes and Misdemeanours’ (London, 1748, 4to).

The following have been erroneously ascribed to Lyttelton: 1. ‘The Persian Letters continued, &c.,’ 3rd edit. London, 1736, 12mo. 2. ‘A Modest Apology for my own Conduct,’ London, 1748, 8vo. 3. ‘New Dialogues of the Dead,’ London, 1762, 8vo. 4. ‘History of England, &c.,’ London, 1764, 12mo, really by Goldsmith.

Several of Lyttelton's poems were printed in Dodsley's ‘Collection,’ London, 1748, 12mo (ii. 3–61), and in the third edition of ‘The New Foundling Hospital for Wit,’ London, 1771, 8vo. Separate collections were published in 1773 (Glasgow, 12mo), 1777 (Glasgow, 24mo), 1785 (London, 12mo), 1795 (London, 12mo), and 1801 (London, 8vo). They will also be found in Anderson's ‘Poets’ (vol. x.), Chalmers's ‘English Poets’ (vol. xiv.), and other anthologies. A number of his pieces were translated into German by J. G. Weigel (Nuremberg, 1791, 8vo).

A collection of his ‘Works,’ both in prose and poetry, was published by his nephew, G. E. Ayscough [q. v.], in 1774 (London, 4to). Other editions were published in 1774 (Dublin, 8vo, 2 vols.), in 1775 (Dublin, 8vo), and ‘the third edition’ appeared in 1776 (London, 8vo, 3 vols.)

[Sir Robert Phillimore's Memoirs and Correspondence of George, Lord Lyttelton, 1845; Ayscough's Works of George, Lord Lyttelton, with portrait, 1776; Walpole's Memoirs of the Reign of George II, 1847; Walpole's Memoirs of the Reign of George III, 1845; Walpole's Letters, 1861, vols. i–v.; Bedford Correspondence, 1843; Chatham Correspondence, 1838–40; Chesterfield's Letters and Works, 1845–53, i. 316–17, 354, v. 204, 426–47; Grenville Papers, 1852–3; Waldegrave's Memoirs, 1821; Memoirs by a Celebrated Literary and Political Character (i.e. Richard Glover), 1814; Dodington's Diary, 1784; Lord Albemarle's Memoirs of Rockingham, 1852; Harris's Life of Lord Hardwicke, 1847; Nash's Worcestershire, 1781, i. 490, 492–3, 504–5, Supplement, 1799, pp. 35–6; Boswell's Life of Johnson, ed. G. B. Hill, 1887; Johnson's Works, 1810, xi. 380–9; Walpole's Cat. of Royal and Noble Authors, 1806, iv. 348–55, with portrait; Nichols's Literary Anecdotes, 1812–15, vi. 457–67 et passim; Quarterly Review, lxxviii. 216–67; Collins's Peerage, 1812, viii. 349–57; Burke's Peerage, 1891, pp. 555, 890, 1343, 1383; Hist. MSS. Commission, 2nd Rep. pp. xi. 36–9; Foster's Alumni Oxon. 1888, iii. 887; Halkett and Laing's Dict. of Anon. and Pseudon. Lit. 1882–8; Notes and Queries, 7th ser. xi. 248, 355.]

G. F. R. B.

Dictionary of National Biography, Errata (1904), p.187

N.B.— f.e. stands for& from end and l.l. for last line

| Page | Col. | Line | |

| 372 | i | 11 | Lyttelton, George, 1st Baron Lyttelton: after chaplain, insert Other literary friends were Glover, James Hammond, and Shenstone, who placed an inscription to him at the Leasowes. |