Samuel Wesley (1662–1735)

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

WESLEY, SAMUEL (1662–1735), divine and poet, father of the great methodist leader, second son of John Wesley, was baptised on 17 Dec. 1662 at Winterborn-Whitchurch, Dorset. The family name was originally spelled Westley, and Samuel so wrote his name in 1694. His grandfather, Bartholomew Westley (1595?–1679?), was the third son of Sir Herbert Westley of Westleigh, Devonshire, by his wife Elizabeth de Wellesley of Dangan, co. Meath. He held the sequestered rectories of Charmouth (from 1640) and Catherston (from 1650), Dorset, from both of which he was ejected in 1662, subsequently practising as a physician; he married (1619) Anne, daughter of Sir Henry Colley of Carbury, co. Kildare, and granddaughter of Adam Loftus (1533?–1605) [q. v.], primate of Ireland; the story that on 23 Sept. 1651 he gave information intended to secure the capture of Charles II, who had lodged at Charmouth after the battle of Worcester, seems authentic, in spite of some difficulty about details (see authorities in Tyerman's Samuel Wesley, pp. 29 sq.; also Miraculum basilicon, 1664, p. 49, by A[braham] J[enings]). His father, John Wesly (his own spelling), Westley, or Wesley (1635?–1678) of New Inn Hall, Oxford (matriculated on 23 April 1651, B.A. on 23 Jan. 1654–5, M.A. on 4 July 1657), was appointed to the vicarage of Winterborn-Whitchurch in May 1658; the report of his interview in 1661 with Gilbert Ironside the elder [q. v.], his diocesan, shows him to have been an independent; he was imprisoned for not using the common prayer-book, ejected in 1662, and died at Preston, near Weymouth, in 1678. His engraved portrait is in the ‘Methodist Magazine’ (1840). He married a daughter of John White (1574–1648) [q. v.], and niece in some way of Thomas Fuller (1608–1661) [q. v.], the church historian; White married a sister of Cornelius Burges or Burgess [q. v.] Wesley's eldest son was Timothy (b. 1659); a younger son, Matthew Wesley, remained a nonconformist, became a London apothecary, and died on 10 June 1737, leaving a son, Matthew, in India; he provided for some of his brother Samuel's daughters.

Samuel Wesley, after passing through Dorchester grammar school, under Henry Dolling, was sent by the independents to be educated for their ministry under Theophilus Gale [q. v.] He reached London on 8 March 1678, shortly after Gale's death, and, after attending another grammar school, was placed (with an exhibition of 30l.) under Edward Veel or Veal [q. v.] at Stepney. Here he remained some two years, proceeding to the academy of Charles Morton (1627–1698) [q. v.] at Newington Green. Being ‘a dabbler in rhyme and faction,’ he was encouraged (but not by Morton) in writing ‘lampoons both on church and state,’ and ‘pasquils’ against Thomas Doolittle [q. v.], head of a rival (presbyterian) academy. Among his forty or fifty fellow students were Timothy Cruso [q. v.], Daniel Defoe [q. v.], and John Shower [q. v.] A ‘reverend and worthy person,’ his relative, who visited him at the academy, first gave him ‘arguments against the dissenting schism.’ John Owen (1616–1683) [q. v.], believing that degrees would soon be open to nonconformists, wished him to study at a university; he went on foot to visit Oxford, ultimately entering as a servitor at Exeter College in August 1683, matriculating on 18 Nov. 1684 (when his age is wrongly given as eighteen), and graduating B.A. on 19 June 1688. While at Oxford he published anonymously through John Dunton [q. v.] a volume of verse, dedicated to his old master, Dolling, and entitled ‘Maggots: or, Poems on Several Subjects, never before handled. By a Schollar’ (1685, 12mo; the frontispiece has a caricature portrait of the author); he also contributed verses to ‘Strenæ Natalitiæ Academiæ Oxoniensis’ (1688, fol.) in honour of the birth of the Pretender.

Wesley's conformity was probably influenced by his admiration of Tillotson, to whose memory he subsequently penned an elegy. It is clear also that he was repelled by the tone of the political dissenter, and found Oxford society more congenial than he expected. He was ordained deacon by Thomas Sprat [q. v.] at Bromley on 7 Aug. 1688; priest, by Henry Compton (1632–1713) [q. v.], at St. Andrew's, Holborn, on 24 Feb. 1689–90. After serving a curacy, and acting as chaplain to a man-of-war, he obtained a curacy in London of 30l. a year, and married (about 1690) Susanna (b 20 Jan. 1669–70; d 23 July 1742), youngest daughter of Samuel Annesley [q. v.], who had already abandoned her father's nonconformity, and ‘had reasoned herself into Socinianism, from which her husband reclaimed her’ (Southey). His wife's grandfather was John White (1590–1645) [q. v.], the centuriator. Her sister, Elizabeth (d. 28 May 1697), was the first wife of John Dunton.

On 25 June 1690 Wesley was instituted to the rectory of South Ormsby, Lincolnshire, in the patronage of the Massingberd family, worth 50l. a year, with a ‘mean cot’ for residence (his first entry in the parish register is dated 26 Aug. 1690). He assisted Dunton in conducting the ‘Athenian Gazette’ (17 March 1691 to 14 June 1697); the articles of agreement between Wesley, Richard Sault [q. v.], and Dunton, are dated 10 April 1691; the numerous answers to the theological and kindred questions are probably Wesley's. Much other literary work was done by him at Ormsby. John Sheffield [q. v.], then Marquis of Normanby, who had made him his chaplain, proposed him for an Irish bishopric in 1694 (Birch, Tillotson, 1753, p. 307; Tillotson spells the name Waseley). In the same year he was incorporated M.A. at Cambridge. He was compelled to resign Ormsby owing to his refusal to allow the visits of the mistress of James Saunderson (afterwards Earl of Castleton), who rented a house in the parish.

In 1695 (Foster) Wesley became rector of Epworth, Lincolnshire, a crown living worth 200l. a year. He was already 150l. in debt, a fact easily accounted for by his growing family, and by his having to contribute to his mother's support. By 1700 his indebtedness had reached 300l., partly owing to losses in farming operations, for which he was unfitted. Several friends, including Gilbert Burnet [q. v.], helped him; and John Sharp (1645–1714) [q. v.], archbishop of York, offered to apply to the House of Lords for a brief in his behalf. This Wesley declined, though his life was henceforth a continuous struggle with pecuniary difficulties. In 1697 his barn had fallen; in July 1702 his rectory was burned; in 1704 a fire destroyed all his flax; in June 1705 he was imprisoned for debt in Lincoln Castle, and lay there several months; in February 1708–9 his rebuilt rectory was burned down with all its contents (among these was the parish register, the loss of which has left uncertainty about the births of some of his children). He continued to ply his pen, publishing both in verse and prose. In 1701 he was first elected to convocation as proctor for the Lincoln diocese; in 1710 he was re-elected, and gave regular attendance so long as convocation was allowed to transact business. A story to the effect that he stayed away from home ‘for a twelvemonth’ prior to the death of William III because his wife refused to say ‘amen’ to the prayer for that sovereign, though vouched for by his son John, is disproved by Tyerman on the evidence of his own letters. He offered his services in 1705, without result, as a missionary to India, China, and Abyssinia. In the same year he published a poem on the battle of Blenheim, which Marlborough acknowledged by bestowing on him the chaplaincy of Colonel Lepell's regiment, but he was not allowed to hold it long, perhaps because the regiment was ordered abroad.

As far back as 1690, after attending a meeting of the Calves Head Club in Leadenhall Street, Wesley had written an account of the inner life of nonconformist academies, in the shape of a letter intended for Robert Clavel [q. v.], but apparently not sent to him by Wesley and not meant to be published. Without Wesley's knowledge or consent, Clavel at length published the document, anonymously, as ‘A Letter from a Country Divine to his Friend in London, concerning the Education of Dissenters in their Private Academies … offered to the Consideration of the Grand Committee of Parliament for Religion’ (1703, 4to). A controversy followed with Samuel Palmer (d. 1724) [q. v.] Wesley's ‘Defence’ (1704) and ‘Reply’ (1707) were in his own name. The ‘Reply’ was revised by William Wake [q. v.], then bishop of Lincoln. There is no doubt that Wesley hits blots in the contemporary nonconformist training and temper, in London especially. The enmity of dissenters is said (but this is doubtful) to have deprived him of his regimental chaplaincy, and disappointed his hopes of a prebend. According to his son John, Wesley wrote the speech delivered at his trial (7 March 1709–10) by Henry Sacheverell [q. v.] During his absence at this time in London his wife supplied deficiencies of Inman, his curate, by reading prayers and a sermon on Sunday evening at the rectory to her family and two hundred of the neighbours.

Towards the close of 1716 the Epworth rectory was the scene of noises and disturbances, lasting till the end of March 1717, and supposed to have a preternatural origin. The account, from family manuscripts which had come into possession of Samuel Badcock [q. v.], was first published in 1791 by Joseph Priestley [q. v.], who speaks of it as ‘perhaps the best authenticated, and the best told story of the kind, that is anywhere extant.’ From 1722 (Foster; and Wesley's own statement) Wesley held in addition to Epworth the small rectory of Wroot, five miles distant; here he sometimes resided, but the addition to his income was inconsiderable. He was accused, and by his brother Matthew, of lax economy; his reply (1731) furnishes a minute history of his affairs, which proves that he had done his best.

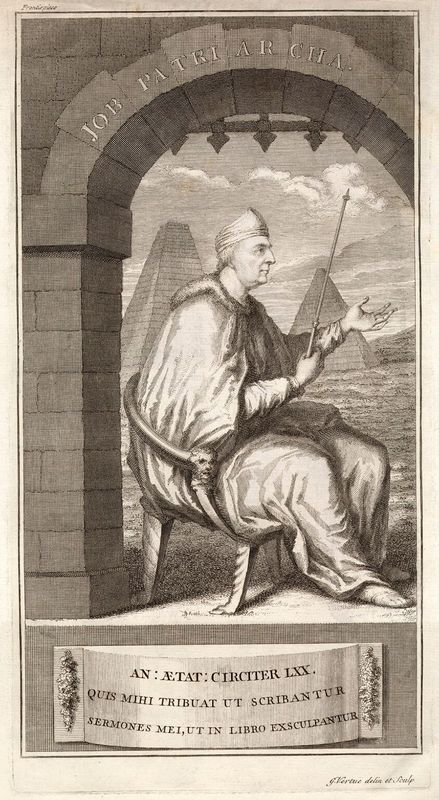

His later years were employed upon an exhaustive work on Job; his first collections for it were destroyed in the fire of 1709. Gout and palsy compelled him to employ amanuenses. Proposals for printing were issued in 1729. Pope wrote (1730) to interest Swift in the subscription list, engaging that ‘you will approve his prose more than you formerly could his poetry.’ The publication was posthumous, ‘Dissertationes in Librum Jobi’ (1735, fol., but most copies have new title-page, and date 1736), with portrait of the author (in fantastic dress, and bearing a sceptre), several plates, and a dedication to Queen Caroline. John Wesley presented a copy to the queen, who remarked, ‘It is very prettily bound.’

On 4 June 1731 Wesley was disabled by being thrown from a waggon, and never recovered his strength. He died at Epworth on 25 April 1735, and was buried in the churchyard. The inscription on his tombstone was renewed 1819, and again 1872, when the tomb was rebuilt. Tyerman has reproduced his portrait, engraved by J. H. Baker, from the frontispiece to ‘Job,’ engraved by Vertue; the portrait-frontispiece to ‘Maggots’ was reproduced (1821) by Thomas Rodd the younger [q. v.] From him his sons inherited their small stature. His widow was buried (1 Aug. 1742) in Bunhill Fields; a poetical epitaph by Charles Wesley implies that his mother had not known true religion before her seventieth year; her gravestone was renewed in 1828; a marble monument to her memory was erected (December 1870) in front of City Road Chapel (for her portrait, see Notes and Queries, 3rd ser. vii. 148). Of his nineteen children the following survived infancy: 1. Samuel, who is noticed below. 2. Emilia (1691–1770?), married Robert Harper, quaker apothecary at Epworth; left early a widow without issue. 3. Susanna (1695–1764), married, 1721, Richard Ellison (d 1760), a man of good estate, from whom she separated; had two sons and two daughters; the descendants of her daughters and younger son have been traced. 4. Mary (1696–1734), married, 1733, John White Lamb, later known as Whitelamb (1707–1769), her father's curate, and died in childbed. 5. Mehetabel (1697–1751), married, 1724, William Wright, a London plumber, of low habits; none of her children survived infancy; her poetical gift was remarkable; her pieces, some of them printed in various magazines and in the lives of her brothers, have never been collected. 6. Anne (b 1702), married, 1725, John Lambert, land surveyor at Epworth, had issue, and was living in 1742. 7. John, who is separately noticed. 8. Martha (1707?–1791), married, 1735, Westley Hall [q. v.]; of her ten children nine died in infancy; Hall was a pupil of John Wesley at Lincoln College, Oxford; he followed the methodist movement for a time, but eventually took to erratic courses in religion and practice, including a more than theoretical adoption of polygamy; Mrs. Hall was a friend of Dr. Johnson, who offered her a home at Bolt Court. 9. Charles, who is separately noticed. 10. Keziah (1710–1741), died unmarried; she had been engaged to Westley Hall. All the daughters of Samuel Wesley showed great ability and were highly educated; three of them were very unfortunate in their marriages.

Wesley's publications, additional to the above-mentioned, were (in verse): 1. ‘The Life of our Blessed Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ: an Heroic Poem. … Ten Books,’ 1693, fol., plates; dedication to Queen Mary, with new title-page, 1694, fol.; revised edition 1697, fol.; abridged edition 1809, 2 vols. 12mo, by Thomas Coke [q. v.]; this poem is said to have brought Wesley his Epworth preferment. 2. ‘Elegies … on the death of … Mary Queen of England … on the death of … John [Tillotson], late Archbishop of Canterbury,’ 1695, fol. 3. ‘An Epistle to a Friend concerning Poetry,’ 1700, fol.; Wesley criticises English poets, especially from the point of view of religion and morals; he admires Blackmore, as ‘big with Virgil's manly thought.’ 4. ‘The History of the Old and New Testament, attempted in Verse,’ 1704, 3 vols. 12mo; engravings by John Sturt [q. v.]; dedicated to Queen Anne; 2nd edit. 1717, 12mo. 5. ‘Marlborough, or the Fate of Europe,’ 1705, fol. Posthumous was 6. ‘Eupolis's Hymn to the Creator,’ first published in the ‘Arminian Magazine,’ 1778; the manuscript is partly in the hand of his daughter, Mehetabel; this circumstance, and the superiority of the poem to Wesley's other verse, suggest joint authorship; John Wesley always claimed the whole for his father.

Also (in prose) 7. ‘Sermon … [Ps. xciv. 16] before the Society for the Reformation of Manners,’ 1698, 8vo; noteworthy as exhibiting his sympathy with efforts of kindred type to those of the early methodist societies. 8. ‘The Pious Communicant Rightly Prepared. … With Prayers and Hymns … added a short Discourse of Baptism,’ 1700, 12mo; appended is ‘A Letter concerning the Religious Societies.’ John Wesley's ‘Treatise on Baptism,’ dated 11 Nov. 1756, is an unacknowledged reprint of his father's ‘Short Discourse,’ slightly retouched. Posthumous was 9. ‘A Letter to a Curate,’ 1735, 8vo; a very able summary of clerical duties and studies. Wesley also compiled for Dunton ‘The Young Student's Library,’ 1692, fol.; workmanlike synopses of eighty-nine works in divinity, history, and science.

Wesley's verse will not lift him high among poets (he was pilloried in the first edition of the ‘Dunciad,’ 1728, i. 115), nor has his ‘Job’ given him his expected rank among scholars. He was an able, busy, and honest man, with much impulsive energy, easily misconstrued; his fame is that of being the father of John and Charles Wesley.

Samuel Wesley the younger (1691–1739), poet, eldest child of the above, was born in Spitalfields on 10 Feb. 1690–1. It is said that he could not speak till he was more than four, and then began with intelligible sentences, but the story is not very credible; nor is the story (Armin. Mag. v. 547) of the mulberry on his neck, which every spring was ‘small and white,’ and then turned green, red, purple, as it grew in size. He entered Westminster school in 1704, and was elected king's scholar in 1707. His bent was for classics; he thought it an irksome break in his studies when Sprat, dean of Westminster, as well as bishop of Rochester, who had ordained his father, took him out to Bromley and used his services as a reader. As a Westminster student he entered Christ Church, Oxford, matriculating on 9 June 1711 (when his age is wrongly given as eighteen). His letter (3 June 1713) to Robert Nelson [q. v.] shows intelligent study of the problem of the Ignatian Epistles. He graduated B.A. in 1715, and M.A. in 1718, and became head usher in Westminster school (his appointment seems to have dated from 1713), and took orders, on the advice of Francis Atterbury [q. v.], who had succeeded Sprat in both offices. His attachment to Atterbury, with whom he corresponded in his exile, and in whose cause he wrote fierce epigrams on Sir Robert Walpole [q. v.], was the real ground for refusing him the post of under-master at Westminster, though the reason assigned was his marriage. To the education of his brothers, ‘both before and since they entered the university,’ he contributed ‘great sums,’ and was ‘very liberal to his parents and sisters’ (letter of his father, 28 Feb. 1733). He was active in promoting (1719) the first infirmary at Westminster, now St. George's Hospital, Hyde Park Corner (Notes and Queries, 4th ser. iii. 353). In 1733 (Foster) he accepted the offer of the mastership of Tiverton grammar school, Devonshire, founded by Peter Blundell [q. v.] He never held any cure; his father in February 1733 was anxious to resign Epworth in his favour, but he declined the proposal. With his brothers John and Charles, while in Georgia, he corresponded in full sympathy (he was interested in the prospects of this colony, and his muse had prophesied its future greatness; he was probably the ‘Rev. Samuel Wesley’ who as early as 1731 gave donations to the Georgia mission, including ‘a pewter chalice and paten,’ Stevenson, p. 254); the opening of their subsequent career he viewed with strong disfavour as the beginning of schism, and he remonstrated with his mother on her countenance of ‘a spreading delusion;’ the members of the family wrote frankly to each other, and Samuel did not spare his sarcasm; but there was no breach of good feeling. Atterbury's patronage, and his own vein of satire and humorous verse, made Wesley known in London literary circles. Edward Harley, second earl of Oxford [q. v.], writes (7 Aug. 1734) that he does not ‘know one so capable’ of annotating Hudibras. Pope obtained subscribers for Wesley's volume of verse, ‘Poems on several Occasions,’ 1736, 4to; enlarged edition 1743, 4to; also Cambridge 1743, 12mo (with prefixed ‘Account of the Author’); reprinted 1808 and 1862. Besides humorous pieces, this contains several hymns of great beauty; five of them are included in the present Wesleyan hymn-book. A previous anonymous publication, ‘The Song of the Three Children,’ 1724, is by Wesley, and many of his pieces were published separately (‘Neck or Nothing,’ 1716, 8vo; ‘The Battle of the Sexes,’ 1724; ‘The Parish Priest,’ 1732; ‘The Christian Poet,’ 1735; ‘The Pig, and The Mastiff,’ 1735) or contributed to magazines. Like his brother John, Samuel was near-sighted, and his health had never been good. He died suddenly at Tiverton on 6 Nov. 1739, and was buried in the churchyard. His portrait has been engraved. He married a daughter of John Berry (d. 1730), vicar of Watton, Norfolk, and had several children, who died in infancy (a memorial tablet to four of them was placed in 1880 in the south cloister of Westminster Abbey), and a daughter, who married Earle, apothecary in Barnstaple. From her family a quantity of Wesley's papers passed into Badcock's hands.

[Tyerman's Life and Times of the Rev. Samuel Wesley, 1866, a careful study, giving many of Wesley's letters; some others are in Tyerman's John Wesley, 1870; Wood's Athenæ Oxon. ed. Bliss, iv. 503; Wood's Fasti, ed. Bliss, ii. 403; Calamy's Account, 1713, p. 280; Calamy's Continuation, 1727, ii. 429–37; Priestley's Original Letters by the Rev. John Wesley and his Friends, 1791; Lives of John Wesley, especially Hampson's, Whitehead's, and Moore's; Clarke's Memoirs of the Wesley Family, 1822; Dove's Biographical History of the Wesley Family, 1833; Beal's Fathers of the Wesley Family, 1852; London Quarterly Review, April 1864 (‘The Ancestry of the Wesleys’); Reliquary, January 1868, p. 188 (Westley Pedigree by Mark Noble, with biting comment); Stevenson's Memorials of the Wesley Family, 1876 (much new information); Kirk's Mother of the Wesleys, 1876; Foster's Alumni Oxon. 1500–1714; Julian's Dictionary of Hymnology, 1892.]

A. G.

Dictionary of National Biography, Errata (1904), p.278

N.B.— f.e. stands for from end and l.l. for last line

| Page | Col. | Line | |

| 317 | i | 53-54 | Wesley, Samuel (1662-1735): omit under Richard Busby [q. v.], |