Tower of London

Names

- Tower of London

- the Towre

- the Tower

Street/Area/District

- Tower Hill

Maps & Views

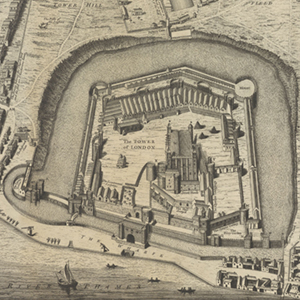

- 1553-59 London (Strype, 1720): The Tower

- 1553-9 Londinum (Braun & Hogenberg, 1572): The Towre

- 1553-9 London ("Agas Map" ca. 1633): The Towre of London

- 1560 London (Jansson, 1657): The Towre

- 1593 London (Norden, 1653 - British Library): Tower of London

- 1593 London (Norden, 1653 - Folger): the Towre

- 1600 Civitas Londini - prospect (Norden): The Towre

- 1600 Civitas Londini - prospect (Norden): The towr

- 1600 ca. Prospect of London (Howell, 1657): The Tower

- 1658 London (Newcourt & Faithorne): Tower of London

- 1666 London after the fire (Bowen, 1772): the Tower

- 1666 Plan for Rebuilding the City (Wren), 1724: Tower

- 1666 Plan for Rebuilding the City (Wren), 1809: Tower of London

- 1666 Prospect of London before & after the fire (Hollar): the Tower, after

- 1666 Prospect of London before & after the fire (Hollar): the Tower, before

- 1677 A Large and Accurate Map of the City of London (Ogilby & Morgan): The Tower

- 1700 Londinum Urbs Praecipua Regni Angliae: The Tower of London

- 1710 Prospect of the City of London, Westminster and St. James' Park (Kip): Tower of London

- 1710 ca. Prospect of London (van Keulen): The Tower

- 1720 London (Strype): Tower

- 1725 London map & prospect (Covens & Mortier): The Tower

- 1736 London (Moll & Bowles): Tower

- 1746 London, Westminster & Southwark (Rocque): The Tower

- 1761 London (Dodsley): Tower

- 1799 London (Horwood): Tower of London

- Map of The Tower Liberty (Strype 1720): The Tower

Descriptions

from A Dictionary of London, by Henry Harben (1918)

Tower of London

Situated at the eastern extremity of the City of London on the north bank of the Thames on Tower Hill (S. 45, and Bayley, ed. 1821, I. p. 1), on the confines of Middlesex and Essex, 1315 (Cal. P.R. 1313–17, p. 314).

The most celebrated fortress in Great Britain, not included within the City boundary. Oldest portion is the White Tower, built by William I. in 1078, Gundulph, bishop of Rochester, being the architect.

It was repaired by William Rufus and Henry I., and restored by Sir C. Wren (S. 45).

In 1190 the wall of the City from the postern to the Thames was broken down to enlarge the Tower and to make a ditch round it (ib.).

Fortified 1239 (S. 47).

Wall and dyke erected round the Tower by Edward I., land being acquired by him for the purpose in East Smithfield from the Hospital of St. Katherine by the Tower (Cal. P.R. Ed. III. 1343–5, p. 84).

Repaired 1532 (S. 49, and Bayley I. 117).

There were two chapels in the Tower, "St. John's Chapel" and "St. Peter ad vincula" (q.v.).

The records of the kingdom were kept in the White Tower until recent times.

Fortifications consisted of the Inner Ward or ballium, and the Outer Ward, together with the wide ditch, or moat, now dry. The Inner Ward was defended by 13 strong Towers, partly square, partly circular, strong and thick, while the Ballium wall was 40 ft. high.

The Towers were named: Bell, Beauchamp or Cobham, Devereux, Flint, Bowyer's, Brick, Jewel, Constable, Broad Arrow, Salt, Lanthorn, Record or Artillery and Bloody Towers (ib. 315).

The defences of the Outer Ward were: Bulwark Gate, Lion Tower, Martin Tower, Byward Tower, St. Thomas' Tower, Cradle Tower, Well Tower, Iron Gate Tower (Britton and Brayley, p. 348).

The Tower is governed by a Constable and was in old days maintained by rents and profits received from tenements within the Tower precincts, tolls from boats and ships, and on fish caught in the Thames (ib. 197–8; and see L. and P. Ed. VI., etc., Vol. I. p. 692).

One half of the Tower, the ditch on the west side and bulwarks, formed part of Tower Ward before the Tower was built (S. 131). The remainder of the precincts were in Portsoken Ward.

The Tower was said to be within the liberty and precinct of the liberty of the City (Cal. L. Bk. I. p. 3, 1399–1400), and at an Inquest in 1321 the second gate of the Tower west is described as in the parish of All Hallows Barking in Tower Ward (ib. note). But it was and always remained outside and independent of the jurisdiction of the City.

Boundaries of the franchise set out in temp. Rich. II. (Lansdowne MS. 155, p. 54).

In later times this question whether the Tower and its precincts formed an independent Liberty was the cause of frequent disputes between the citizens of London, the King and the Officers of the Tower. The decision went against the City in 1555, and again in 1613 and 1679, when the Liberties were defined by Orders in Council. James II. confirmed these privileges by Charter, and again defined the boundaries (Bayley, II, 670–1, and App. cxviii.).

The Liberties set out in these patents included the Little Minories, the Old Artillery Ground, and Well Close (Bayley, II. cxviii.).

The circumference of the Tower is set out in this Patent, and some of the bounds indicated can be identified on the older maps.

See Tower Liberty.

Tradition says that there was a tower on this site in Roman times, and in 1772–7, when excavations were being made, the ruins of an old wall were found to the south-east of the White Tower, forming a portion of the old City Wall, and also some Roman coins. A portion of the wall of the Roman city was also found built into the Wardrobe Tower, the plinth of the existing wall being above the present level of the ground. The discovery of portions of the wall in this neighbourhood furnish evidence of the determination of William I. to erect his fortress within the City boundary as a sign and symbol of his authority.

Roman remains have also been found near Cold Harbour Tower.

from A New View of London, by Edward Hatton (1708)

Tower of London, situate betn the S.E. end of the City Wall and the Thames, tho' the W. part, so far as the White Tower, is supposed within the City, but with some uncertainty, and in what County the whole stands is not easily discovered. The White Tower is 800 Yards Ed from London-Bridge, situate near the River Banks, and is said to have been built by Julius Cæsar, but others with more probability of Veracity tell us, it was first erected by William the Conqueror, Anno 1078, who appointed Dundulph then Bishop of Rochester Surveyor of that Work. This Tower being in time enlarged with other Buildings for the use of such as belong to the Church, the Mint, the Arsenal, Ordnance, the Governour, Prison, Warding, &c. appears now liker a Town than a Tower, and is surrounded with a Wall and a Ditch which in some places is 120 Foot broad.

The places of most note within which are the Church, the White Tower, the Offices of Ordnance, of the Mint, of the Keepers of the Records, the Jewel House, the Horse Armory, the Grand Store-house, the New or Small Armory, and some other Store-houses.

The principal Officer is the Constable of the Tower (of which there have been none of late.) 2d. The Lieutenant of the Tower, who in absence of a Constable is invested with all manner of power relating to the Government hereof, and (as the Constable) is in the Commission of the Peace for the Counties of Middlesex, Surry and Kent, the present Lieutenant who has that Office of great Power and Trust is the honourable Brigadeer Gen. Cadogan, Esq; whose Salary is 200 l. per An. besides Perquisites. Here are also a Deputy Lieutenant, now Coll. Farrel; also the Tower Major, 1 Gent. Porter, 1 Chaplain, 1 Physician, 1 Gent. Goaler, 1 Apothecary, 1 Surgeon, 1 Yeoman Porter, 2 Master Gunners and 4 other Gunners besides the Water Pumper, Scavenger and Clock-keeper, and 40 Wardens for the better conservation not only of the Jewels, Money, Plate, Magazines, &c. but also of the Peace and Government of this place as a Prison; for which Prison see Sect. the 6. following, Offices of the Mint, Court and Office of Records see Sect. the 5th: And as for the Ordnance, Stores, and the Artillery; the Arsenal and Armories, the Jewel House, &c.

from A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, by John Strype (1720)

[Tower of London]

| Of the Situation and Magnitude of this Great Fortress, the TOWER. | |

| It is situate upon a large Plot of Ground, called the Tower Liberty, which contains both the Tower Hills, viz. the greater and the lesser, and Part of East Smithfield, Rosemary Lane, Well-Close, &c. | How situate. R. B. |

| It is encompassed with a broad and deep Ditch, supplied with Water out of the Thames, which is its Southern Bounds; and over this Ditch it hath Two Bridges, one for Carts and Coaches, by the Lions Tower; and the other for Foot-Passengers, over a Draw-Bridge on the South side. Besides, it hath a Passage, or Cut out of the Thames, which is called Traitors Bridge; so called, for that formerly all Persons committed to the Tower for Treason, were brought through thither by Boat. The Piece of Ground on which the Tower stands, contains Twenty six Acres, a Rod, and something more. | Its Extent. |

| The Compass about the Tower, on the Outside of the Ditch, is 3156 Foot. And the Quantity of Ground comprehended within the Walls and Ditch, is Twelve Acres, and odd Rods. The whole, with its Liberty as aforesaid, contains something above Twenty six Acres of Ground. | Its Compass. |

| A Sight of this Tower is here represented, taken from the River of Thames, and an Ichnographical Ground Plot; in which you may see the Position and Situation of the several Places mentioned in this Discouse of the Tower; all of them being either express'd by Letters, or Figures, according to this following Table; which is a better Satisfaction to the Reader, than a Multitude of Words. | A Plan of the Tower. |

| Table of References Places noted in the Ground-Plot; are, |

|

|

| The other Places, which have no Names nor Figures set to them, are Dwelling Houses belonging to the Warders, and other Officers, of the Tower.] Whereas the Tower is said to be within the City of London, it is (saith Lord Coke) thus to be understood: That the Ancient Wall of London (the Mention whereof yet appeareth) extendeth through the Tower: And all that which is environed with the said Wall, viz. on the West Part thereof, is within the City of London; that is to say, in the Parish of All Saints Barking, within the Ward of the Tower. And the Residue of the Tower on the East Part of the Ancient Wall, is within the County of Middlesex. And this, upon View and Examination, was found out, Mic. 13. Jacob. Regis, in the Case of Sir Thomas Overbury, who was poisoned in a Chamber in the Tower, on the West Part of that old Wall. And therefore Weston, the principal Murtherer, was tried before Commissioners of Oyer and Terminer in London; and so was Sir Gervase Elways, Lieutenant of the Tower, as accessary. | Tower, how within the City. Coke Instit. P. 4. J. S. |

| And here it will be proper to take some View of the Liberties; that is, of some certain Extent of Ground bordering upon the Tower; to which was annexed a peculiar Liberty, viz. to be subject to no Jurisdiction but that of the Tower it self. This, being upon the Confines of the City, hath occasioned sometimes great Difference between the Tower-Officers, and the Maior and City of London. As in the Fifth of Edward IV. in the First of Q. Elizabeth, also in the Year 1585; as shall be shewn more at large in the Chapter for Towerstreet Ward. … | The Liberties of the Tower. J. S. |

| it appears, that the Precinct of the Tower begins at the Tower Dock, and extends unto the End of Towerstreet; and so is described to lye Juxta Barking Church on the Westside; Juxta Crutched Friars on the North; Juxta S. Mary Graces, and St. Katharines on the East. Juxta can have no other Construction but corjuuctim; so as there cannot be any Thing Interpositum, i.e. put between. And therefore London is secluded to have any Soil or Liberty between Barking Church, and Crutched Friars, St. Mary Graces, and St. Katharines. | Precinct of the Tower. |

| Add this concerning the Extent of the Maior and Cities Cognizance of Crimes done hereabouts: that there is a Roll in the Tower Records, viz. That Transgressions done infra Portam exteriorem, i.e. beneath the Outer Gate of the Tower, be not drawn before the Maior and Sheriffs of London. Pro Willimo. Finchinfeld. … The Antiquity and First Buildings. | |

| It hath been the common Opinion, and some have written, (but of none assured Ground) that Julius Cæsar the first Conqueror of the Britains, was the original Author and Founder as well thereof, as also of many other Towers, Castles and great Buildings within this Realm. But (as I have already before noted) Cæsar remained not here so long; nor had he in his Head any such Matter, but only to dispatch a Conquest of this barbarous Country, and to proceed to greater Matters. Neither do the Roman Writers make mention of any such Buildings Erected by him here. | Julius Cæsar reported the Founder. In my Annals. |

| And therefore leaving this, and proceeding to more grounded Authority, I find in a fair Register Book of the Acts of the Bishops of Rochester, set down by Edmond of Hadenham, that William the First (surnamed Conqueror) Builded the Tower of London; to wit, the great White and Square Tower there, about the Year of Christ 1078, appointing Gundulph, then Bishop of Rochester, to be principal Surveyor and Overseer of that Work; who was for that Time lodged in the House of Edmere a Burgess of London. The very Words of which mine Author are these; Gundulphus Episcopus mandato Willielmi Regis magni præfuit Operi magnæ Turris London. Quo Tempore hospitatus est apud quendam Edmerum Burgensem London. Qui dedit unum Were Ecclesiæ Roffen. | William the Conqueror built the White Tower, Anno 1078. |

| Ye have heard before, that the Wall of this City was all round about furnished with Towers and Bulwarks, in due Distance every one from other; and also that the River of Thames, with his Ebbing and Flowing, on the South side had subverted the said Wall and Towers there. Wherefore, it is supposed, King William, for defence of this City, in Place most dangerous and open to the Enemy, having taken down the second Bulwark in the East Part of the Wall from the Thames, Builded this Tower, which was the great square Tower (now called the White Tower) and hath been since at divers Times enlarged with other Buildings adjoining, as shall be shewed hereafter. |

from London and Its Environs Described, by Robert and James Dodsley (1761)

Tower of London, on the east side of the city, near the Thames. This edifice, at first consisted of no more than what is at present called the White Tower; and without any credible authority, has been vulgarly said to have been built by Julius Cæsar; though there is the strongest evidence of its being marked out, and a part of it first erected by William the Conqueror in the year 1076, doubtless with a view to secure to himself and followers a safe retreat, in case the English should ever have recourse to arms to recover their liberties. That this was the Conqueror's design, evidently appears from its situation on the east side of London, and its communication with the Thames, whence it might be supplied with men, provisions, and military stores, and it even still seems formed for a place of defence rather than offence.

However the death of the Conqueror in 1087, about eight years after he had begun this fortress, for some time prevented its progress, and left it to be completed by his son William Rufus, who in 1098 surrounded it with walls, and a broad and deep ditch, which was in aome places 120 feet wide, several of the succeeding Princes added additional works, and Edward III. built the church.

Since the restoration, it has been thoroughly repaired: in 1663 the ditch was scoured; all the wharfing about it was rebuilt with brick and stone, and sluices made for letting in and retaining the Thames water as occasion may require: the walls of the White Tower, have been repaired; and a great number of additional buildings have been added. At present, besides the White Tower, are the offices of Ordnance, of the Mint, of the keepers of the records, the jewel office, the Spanish armoury, the horse armoury, the new or small armoury, barracks for the soldiers, handsome houses for the chief officers residing in the Tower, and other persons; so that the Tower now seems rather a town than a fortress. Lately new barracks were also erected on the Tower wharf; and the ditch was in the year 1758, railed round to prevent for the future those melancholy accidents which have frequently happened to people passing over Tower-hill in the dark.

The Tower is in the best situation that could have been chosen for a fortress, it lying only 800 yards to the eastward of London bridge, and consequently near enough to cover this opulent city from invasion by water. It is to the north of the river Thames, from which it is parted by a convenient wharf and narrow ditch, over which is a drawbridge, for the readier taking in or sending out ammunition and naval or military stores. Upon this wharf is a line of about sixty pieces of iron cannon, which are fired upon days of state.

Parallel to this part of the wharf upon the walls is a platform seventy yards in length called the Ladies line, from its being much frequented in summer evenings by the ladies, as on the inside it is shaded with a row of lofty trees, and without affords a fine prospect of the shipping, and of the boats passing and repassing the river. The ascent to this line is by stone steps, and being once upon it, you may walk almost round the Tower walls without interruption, in doing which you will pass three batteries, the first called the Devil's battery, where is a platform, on which are mounted seven pieces of cannon: the next is named the Stone battery, and defended by eight pieces of cannon; and the last, called the Wooden battery is mounted with six pieces of cannon: all these are brass, and nine pounders.

But to return to the wharf, which is divided from Tower-hill at each end, by gates opened every morning for the convenience of a free intercourse between the respective inhabitants of the tower, the city, and its suburbs. From this wharf is an entrance for persons on foot over the drawbridge, already mentioned; and also a water gate under the Tower-wall, commonly called Traitor's Gate, through which it has been customary, for the greater privacy, to convey traitors and other state prisoners by water, to and from the Tower: the water of the ditch having here a communication with the Thames, by means of a stone bridge on the wharf. However the Lords committed to the Tower for the last rebellion, were publicly admitted at the main entrance. Over this water-gate, is a regular building terminated at each end by a round tower, on which are embrasures for cannon, but at present none are mounted there. In this building are an infirmary, a mill, and the water-works that supply the Tower with water.

The principal entrance into the Tower is by two gates to the west, one within the other, and both large enough to admit coaches and heavy carriages. Having passed thro' the first of these you proceed over a strong stone bridge, built over the ditch, which on the right-hand leads to the lions tower, and to a narrow passage to the draw bridge on the wharf, while on the left-hand is a kind of ftreet in which is the Mint. The second gate is at a small distance beyond the lions tower, and is much stronger than the first, it has a port-cullis to let down upon occasion, and is guarded not only by some soldiers, but by the warders of the Tower, whose dress and appearance will be immediately described.

The Officers of the Tower. The principal of these to whom the government of the Tower is committed, are, first the Constable of the Tower, who has 1000l. per annum, and is usually a person of quality, as his post at all coronations and state ceremonies, is of the utmost importance, and as the crown and other regalia are in his cuftody: he has under him a Lieutenant, and a deputy Lieutenant; these officers are likewise of great dignity; the first has 700l. a year, and the last, who is commonly called the Governor of the Tower, has 1l. a day. The other officers are, a tower-major, a chaplain, a physician, a gentleman-porter, a yeoman-porter, a gentleman-jailer, four quarter-gunners, and forty warders, who wear the same uniform as the King's yeomen of the guard. They have round flat crowned caps, with bands of party-coloured ribbands: Their coats, which are of a particular make, but very becoming, have large sleeves, and very full skirts gathered round, somewhat in the manner of a petticoat. These coats are of fine scarlet cloth, laced round the edges and seams with several rows of gold lace, and girt round their waists with a broad laced girdle. Upon their breasts and backs they wear the King's silver badge, an embroidered thistle and rose, and the letters G.R. in very large capitals.

The ceremony at opening and shutting the gates. This is done every morning and night with great formality. A little before six in the morning in summer, and as soon as it is well light in winter, the yeoman-porter goes to the Governor's house for the keys, and from thence proceeds back to the innermost gate, attended by a serjeant and six of the main guard. This gate being opened to let them pass, is again shut; while the yeoman-porter and the guard proceed to open the outermost gates, at each of which the guards rest their firelocks, as do the spur guard, while the keys pass and repass. The yeoman-porter then returning to the innermost gate, calls to the warders in waiting to take in King George's keys; whereupon the gate is opened, and the keys lodg'd in the warders hall, till the time of locking them up again, which is usually about ten or eleven at night, with the same formality as when opened. After they are shut, the yeoman and guard proceed to the main guard, who are all under arms, with the officers upon duty at their head. The usual challenge from the main guard is, Who comes here? To which the yeoman-porter answers The keys. The challenger returns Pass keys, and the officer orders the guard to rest their firelocks; upon which the yeoman-porter says, God save King George, and Amen is loudly answered by all the guard. The yeoman-porter then proceeds with his guard to the Governor's, where the keys are left; after which no person can go out, or come in upon any pretence whatsoever till the next morning, without the watch-word for the night, which is kept so secret, that none but the proper officers, and the serjeant upon guard, ever come to the knowledge of it for it is the same on the same night, in every fortified place throughout England. But when that is given by any stranger to the centinel at the spur-guard, or outer gate, he communicates it to his serjeant, who passes it to the next on duty, and so on till it comes to the Governor, or commanding officer, by whom the keys are delivered to the yeoman-porter, who, attended as before, the main guard being put under arms, brings them to the outer gate, where the stranger is admitted, and conducted to the Governor; when having made known his business, he is conducted back to the outer gate; and dismissed, the gate shut, and the keys delivered again with the same formality as at first. It is happy for us that all this seems mere form and parade; but it is however fit that all this ceremony should be duly observed.

from Lockie's Topography of London, by John Lockie (1810)

Tower,—on the N. side the River Thames, near ⅓ of a mile below London-bridge.

from A Topographical Dictionary of London and Its Environs, by James Elmes (1831)

Tower of London, The, is on the eastern side of the city, by the side of the Thames, between the eastern end of Lower Thames-street and St. Katherine's.

The earliest account of any fortification on this site, was a small fortress thrown up by William the Norman, in 1076, who, according to Stow, also built, in 1078, that portion which is called the White Tower and appointed Gundulph, Bishop of Rochester, the most celebrated architect of that period, to superintend the work. William Rufus added a castellated tower on the south side, and it was first enclosed by William Longchamp, Bishop of Ely, who, under pretence of guarding against the designs of John the king's brother, surrounded it with embattled walls, and the present ditch.

In 1239, according to Matthew Paris, Henry III. added to its fortifications, and it is thought that Henry I. built the Lion's Tower, as Strype mentions it in alluding to the additions made by Edward IV.; and it is known that he introduced the menagerie, which had been formerly kept at Woodstock. Richard III. made some additions to the Tower, and Henry VIII. repaired the White Tower, which was rebuilt in 1638, and after the restoration it was thoroughly repaired under the superintendence of Sir Christopher Wren, and a great number of additional buildings made to it. In 1663, the ditch was cleansed, all the wharfing about it was rebuilt of brick and stone, and sluices made for admitting and retaining the Thames water, as occasion might require.

During some repairs under Sir Christopher Wren, in 1675, the remains of what were supposed to be the two young princes, who were smothered in the Tower by order of Richard III., were discovered, about ten feet below the surface of the ground, in a wooden chest. Wren was ordered, as appears from a manuscript book of orders of the Privy Council, which formerly belonged to the Editor of this work, and is quoted in his Life of Wren, to prepare a tomb with the inscription, which being approved by the king in council, was erected in the north aisle of Henry the Seventh's chapel, Westminster.

In 1695, Wren reported to the Council the condition of the Tower and its fitness to receive prisoners of state; the reports of which are printed from the above named manuscripts, in the life of that architect.

The present area of the Tower within the walls, its twelve acres and five poles, and the circuit outside of the ditch, 1052 feet. The principal objects of curiosity within the Tower, are, the menagerie of wild beasts in the Lion tower, the Jewel Office, the armoury, the White tower, the ancient chapel and church (see St. Peter ad Vincula), the Record office, the Beauchamp tower, the Bloody tower, Traitors'-bridge, and the Mint (see that article), to which the public are admitted by fixed gratuities to the warders who shew them.

The Tower is still used as a state prison, and is under the government of the Duke of Wellington, Constable; General William Loftus, Lieutenant; Lieut.-Colonel Sir F.H. Doyle, Bart., Deputy Lieutenant; Captain John H. Elrington, Fort Major; the Rev. Andrew Irvine, M.A., Chaplain; Charles Murry, Esq., Gentleman Porter; Joseph Turtle, Gentleman Jailer; Burg Tomkins, M.D., Physician; — — Surgeon; James Kirtland, Apothecary; Louis Gruaz, Yeoman Porter; Thomas B. Ricketts, Esq., Steward of the Tower, the Ancient Court of Record, His Majesty's Court Leet and Coroner; Thomas Morice, Esq., Deputy Steward; David H. Stable, Esq., Clerk of the Peace; and James W. Lush, Chief Bailiff.

from London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions, by Henry Benjamin Wheatley and Peter Cunningham (1891)

Tower (The) of London, the most celebrated fortress in Great Brtain, stands immediately without the City walls, on the left or Middlesex bank of the Thames, about ⅓ mile below London Bridge.

This Tower is a citadel to defend or command the city; a royal palace for assemblies or treaties; a prison of state for the most dangerous offenders; the only place of coinage for all England at this time; the armoury for warlike provisions; the treasury of the ornaments and jewels of the crown; and general conserver of the most records of the King's courts of justice at Westminster.—Stow, p. 23.

Tradition has carried its erection many centuries earlier than our records:—

This way the king will come, this is the way

To Julius Caesar's ill-erected Tower.

Shakespeare, King Richard II., Act v. Sc. I.

Prince. Where shall we sojourn till our coronation?

Gloster. Where it seems best unto your royal self.

If I may counsel you, some day or two

Your highness shall repose you at the Tower.

Prince. I do not like the Tower, of any place.

Did Julius Caesar build that place, my lord?

Buck. He did, my gracious lord, begin that place,

Which, since, succeeding ages have re-edified.

Prince. Is it upon record, or else reported

Successively from age to age, he built it?

Buck. Upon record, my gracious lord.

Shakespeare, King Richard III., Act iii. Sc. I.

Ye towers of Julius, London's lasting shame,

With many a foul and midnight murder fed.

Gray, The Bard.

There is no authority, however, to confirm tradition in the remote antiquity assigned to the Tower. No part of the existing structure is of a date anterior to the keep, or the great square tower in the centre called the White Tower, and this, it is well known, was built by Willam the Conqueror, circ. 1078. During excavations made for building purposes in 1772 and 1777 some ruins of an old stone wall 9 feet in thickness, and of which the cement was exceedingly hard, were found near the White Tower, and these were either the remains of an earlier edifce, or a portion of the bulwarks of the old wall. Some old Roman coins were also found at the same time.

I find in a fair register book, containing the acts of the Bishops of Rochester, set down by Edmond de Hadenham, that William I., surnamed Conqueror, built the Tower of London, to wit, the great white and square tower there, about the year of Christ 1078, appointing Gundulph, then Bishop of Rochester, to be principal surveyor and overseer of that work.—Stow, p. 17.

Rochester Castle has been commonly ascribed to Gundulph, Bishop of Rochester (the William of Wykeham of his age), but it is now known to be of later date. The keep (now a shell) of the castle at Malling is the only known example left of his military architecture.

The Tower is surrounded by a dry ditch, capable of being flooded at high water, running all round the outer wall. The western, northern and eastern sides are protected by casemated ramparts rising from tie ditch, with bastions at the angles, and surmounted with short heavy guns. The defence along the southern or river front consists of a low rampart, guarded by a chain of small forts.

The "Ballium wall," of great thickness and solidity, and varying from 30 to 40 feet in height, is probably of about the same date as the White Tower. It formerly formed a continuous inner bulwark, but when Cromwell obtained possession of the Tower he caused the Royal Palace, which occupied the south-eastern portion of the space enclosed by this wall, to be pulled down, and with this went a great part of the Ballium wall on the eastern and southern sides. The wall has lately been rebuilt on the eastern side. The only vestige of the Palace left is the buttress of an old archway adjoining the Salt Tower. This inner wall was flanked with thirteen protecting towers, of which twelve still remain in a more or less "restored" form. The Lanthorn Tower, which stood between the Salt and Wakefield Towers, was removed on the erection of the Ordnance Office. In 1882 these warehouses were removed, and the Lanthorn Tower rebuilt, the general effect of the buildings from the river being thus greatly improved.

The principal entrance to the Tower is from Great Tower Hill, at the south-east angle of the outer wall, through the Middle and Byward Towers. The Lion Tower formerly stood just without the Middle Tower, and it was here the Menagerie was kept. On the south or river front are two entrances, the Queen's Stairs by the Byward Tower, and Traitors' Gate, under St. Thomas Tower (used only for the reception of prisoners of rank).

On through that gate misnamed, through which before

Went Sidney, Russell, Raleigh, Cranmer, More.

Roger's Human Life.

At the south-east angle is the Irongate, "a great and strong gate, but not usually opened," facing Little Tower Hill.

The White Tower was restored by Sir Christopher Wren, who faced the windows with stone in the Italian style and otherwise modernised the exterior, but the interior has been but little altered. This Tower is 116 feet from north to south by 96 from east to west, and is three storeys high. The exterior walls are 15 feet in thickness, and the interior is divided by a wall 7 feet thick, running north and south; another running east and west subdivides the eastern of these divisions into unequal parts. These partition walls, extending through all three storeys, form one large and two smaller rooms on each floor. The smallest division of the ground floor, known as Queen Elizabeth's armoury, is a vaulted room, and in reality forms the crypt of St. John's Chapel. On the north side of this room is a cell 10 feet long and 8 wide in the thickness of the wall, and receiving light only through the doorway. These rooms are said to have been Sir Walter Raleigh's prison, where he wrote the History of the World. Over this room, on the first floor, and extending through both first and second floors, is St. John's Chapel, one of the finest specimens of Norman ecclesiastical architecture which we possess. The massive columns and general simplicity of character of this chapel give it a very solemn and impressive appearance. A triforium, extending over the aisles and semicircular east end, probably served to allow the queen and her ladies to attend the celebration of mass unseen by the congregation below. The chapel is 55 feet in length, 31 feet wide, and 32 feet high to the crown of the vault. The nave between the pillars is 14 feet 6 inches wide; the aisles are about half the width, and 13 feet 6 inches high. The triforium is 11 feet 9 inches high. It was dismantled in 1558. At the foot of the winding stairs leading up to St. John's Chapel and situate in the centre of the south side of the White Tower, two skeletons were found in July 1674, supposed to be the remains of the two murdered princes, sons of Edward IV. They were removed in 1678 by Charles II.'s orders to Westminster Abbey, and placed in a small sarcophagus against the east wall of the north side of Henry VII.'s chapel.

St. John's Chapel was long used as a repository for records, but on the erection of the Record Office the records were transferred thither in 1857, and the chapel once more dedicated to its proper uses, divine service being now occasionally celebrated therein. It was in this chapel that, at the creation of the Order of the Bath by Henry IV. at his coronation, the forty-six noblemen and gentlemen first installed knights thereof performed the chivalrous ceremony of watching their armour from sunset to sunrise. Here, kneeling at his prayers before the altar, Brackenbury is said to have received and rejected Richard's proposal to murder the young princes. And here the remains of Elizabeth of York, Queen to Henry VII., lay in state in 1503 previous to her magnificent funeral. The Council Chamber, in the second storey, and communicating directly with the triforium of the chapel, was the old council room of the English Sovereigns. Here Richard II. was compelled formally to resign his crown to Henry of Bolingbroke.

I have been King of England, Duke of Aquitaine and Lord of Ireland about twenty-one years, which seigniory, royalty, sceptre, crown, and heritage I clearly resign here to my cousin Henry of Lancaster; and I desire him here in this open presence, in entering of the same possession, to take this sceptre.—Froissart.

Here also was Hastings denounced, arrested and hurried to the block by Crookback Richard: the gallery which, cut in the solid wall, runs round the whole of the Council Chamber probably serving as the hiding-place for the soldiers whom Richard had in readiness to carry out his foul plans. The vaults of this Tower formed dungeons of the most dismal kind. Here was one called by the suggestive name of "Cold Harbour"; another "Little Ease," where Guy Fawkes was for some time confined, was a mere hole in the wall closed by a heavy door, and was so small that the prisoner could neither stand upright nor lie down, but was obliged to remain in a bent and cramped position. In another of these dungeons was placed the rack, and here the victims could be tortured without fear of their cries being heard. The principal tower in the outer line of defence is the St. Thomas Tower, a fine old edifice, under which extends the wide stone archway, guarded by two strong water-gates, already mentioned as Traitors' Gate. From the landing-place here a flight of stone steps leads to the gate of the Bloody Tower. The heavy portcullis of this latter gateway is one of the very few still to be found in England in working order. The Bloody Tower, the only rectangular tower of the inner ward, is the traditional scene of the murder of the young princes Edward and Richard. The Bell Tower is asserted to have been Elizabeth's lodging when confined in the Tower by her sister: here also Bishop Fisher is said to have been confined; but during the restoration of the White Tower a few years ago a small cell was discovered in the vaults with an inscription, pointing to the White Tower as the Bishop's more probable prison. The Beauchamp or Cobham Tower was probably built about the beginning of the 13th century, and received its name from Thomas de Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, confined here in 1397 previous to his banishment to the Isle of Man. This tower was for many years the principal state prison, and the walls of the prison room (with its two recesses probably formerly used as cells) on the first floor are covered with inscriptions chiselled in it by various occupants. Amongst the innumerable prisoners from time to time confined here may be mentioned: Anne Boleyn (in the upper chamber) 1554; John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, eldest son of the Duke of Northumberland, condemned to death for his part in the conspiracy to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne, was reprieved but died shortly afterwards in his prison room: he left a most elaborate carving, in which his brothers Ambrose, Robert, Guilford, and Henry are symbolised by twigs of oak with acorns, roses, geraniums and honeysuckle. Guilford Dudley, 1554; and Lady Jane Grey (who probably inscribed her name "Jane" on the north wall), 1554; Edmund and Arthur Poole (the great grandsons of George, Duke of Clarence and brother of King Edward IV.), who were confined here from 1562 till their death; Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel, confined here from 1584 to his death in 1595; his body was buried in St. Peter's ad Vincula, but removed to Arundel in 1624; Dr. John Store, Chancellor of Oxford under Queen Mary, and noted for his cruel persecution of the Protestants, executed at Tyburn for high treason 1571, etc. etc. The Devereux Tower, standing at the north-west angle of the inner Ballium wall, derives its name from Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. The Flint Tower, of which all but the foundation walls are of modern date, contained dungeons of such a rigorous character as to receive the designation of Little Hell. The Bowyer Tower, formerly the residence of the King's Bowyer or "Master Provider of the King's Bows," is the reported scene of the murder of George Duke of Clarence in 1474. The fire of 1841, which destroyed the barracks and great storehouse, originated in the Bowyer Tower. The Brick Tower is assigned as the place of confinement of Lady Jane Grey during a portion of the period of her incarceration. In the Jewel or Martin Tower the Crown jewels were formerly kept; it also served as a prison-house. The Constable and Broad Arrow Towers served the same purpose. The Salt Tower is probably of Norman origin, and contains the curious sphere with the signs of the zodiack engraved on its walls, May 30, 1561, by Hugh Draper of Bristol, committed on a charge of sorcery. The Wakefield Tower, which received its name from the imprisonment of the Yorkists after the battle of Wakefield, is now the receptacle for the jewels.

The Jewel House within the Tower was kept by a particular officer called "The Master of the Jewel House." He was charged with the custody of all the Regalia, had the appointment in his gift of goldsmith to the King, and "was even esteemed the first Knight Bachelor of England, and took place accordingly."1 The office was held by Thomas Cromwell, afterwards Earl of Essex. The perquisites and profits were formerly very large, but after the Restoration they diminished so much that Sir Gilbert Talbot, the then Master, was tacitly permitted by the King to show the Regalia to strangers.

The Master of the Jewel House hath a particular Servant in the Tower intrusted with that great Treasure, to whom (because Sr Gilbert Talbot was retrenched in all the perquisites and profitts of his place, and not able to allow him a Competent Salary) his Majesty doth tacitly allow him that he shall shew the Regalia to Strangers; which furnished him with so plentifull a livelyhood that Sr Gilbert Talbot, upon the death of his Servant there, had an offer made to him off 500 old broad peeces of gold for the place.—Harl. MS., 6859, p. 29.

The treasures of the jewel house were diminished during the Civil Wars under Charles I. The plate amongst the Regalia "which had crucifixes or superstitious pictures" was disposed of for the public service;2 and what remained of the plate itself was subsequently delivered up to the trustees for sale of the King's goods to raise money for the service of Ireland.3 The Regalia is arranged in the centre of a well-lighted room, with an ample passage for visitors to walk round. Observe—St. Edward's Crown, made for the coronation of Charles II. to replace the old crown (lost in the confusion of the Civil Wars), which Edward the Confessor was supposed to have worn, and used in the coronations of all our Sovereigns since his time. This is the crown placed by the Archbishop of Canterbury on the head of the Sovereign at the altar, and the identical crown which Blood stole from the Tower on May 9, 1671. The New State Crown, made for the coronation of Queen Victoria; composed of a cap of purple velvet, enclosed by hoops of silver, and studded with a profusion of diamonds; it weighs one pound and three-quarters. The large unpolished ruby is said to have been worn by Edward the Black Prince; the sapphire is of great value, and the whole crown is estimated at; £111,900. The Prince of Wales's coronet, of pure gold, unadorned by jewels. The Queen Consort's Crown, of gold, set with diamonds, pearls, etc. The Queen's Diadem, or circlet of gold, made for the coronation of Mary of Modena, Queen of James II. St. Edward's staff, of beaten gold, 4 feet 7 inches in length, surmounted by an orb and cross, and shod with a steel spike. The orb is said to contain a fragment of the true Cross. The Royal Sceptre, or Sceptre with the Cross, of gold, 2 feet 9 inches in length; the staff is plain, large table diamond; The Rod of Equity, or Sceptre with the Dove, of gold, 3 feet 7 inches in length, set with diamonds, etc. At the top is an orb, banded with rose diamonds, and surmounted with a cross, on which is the figure of a dove with expanded wings. The Queen's Sceptre with the Cross, smaller in size, but of rich workmanship, and set with precious stones. The Queen's Ivory Sceptre (but called the Sceptre of Queen Anne Boleyn), made for Mary of Modena, consort of James II. It is mounted in gold, and terminated by a golden cross, bearing a dove of white onyx. Sceptre found behind the wainscoting of the old Jewel Office in 1814; supposed to have been made for Queen Mary, consort of William III. The Orb, of gold, 6 inches in diameter, banded with a fillet of the same metal, set with pearls, and surmounted by a large amethyst supporting a cross of gold. The Queen's Orb, of smaller dimensions, but of similar fashion and materials. The Sword of Mercy, or Curtana, of steel, ornamented with gold, and pointless. The Swords of Justice, Ecclesiastical and Temporal. The Armillæ, or Coronation Bracelets, of gold, chased with the rose, fleur-de-lys, and harp, and edged with pearls. The Royal Spurs, of gold, used in the coronation ceremony whether the Sovereign be King or Queen. The Ampulla for the Holy Oil, in shape of an eagle. The Gold Coronation Spoon, used for receiving the sacred oil from the ampulla at the anointing of the Sovereign, and supposed to be the sole relic of the ancient regalia.1 The Golden Salt Cellar of State, in the shape of a castle. Baptismal Font, of silver gilt, used at the christening of the Royal children. Silver Wine Fountain, presented to Charles II. by the corporation of Plymouth.

The Tower Menagerie was one of the sights of London up to the reign of William IV. and the removal of the few animals that remained to the Zoological Gardens in the Regent's Park. Henry I. kept lions and leopards, and Henry III. added to the collection.

I read that in the year 1235, Frederick the emperor sent to Henry III. three leopards, in token of his regal shield of arms wherein those leopards were pictured; since the which time those lions and others have been kept in a part of this bulwark [the Tower], now called the Lion Tower, and their keepers there lodged. King Edward II., in the 12th of his reign, commanded the Sheriffs of London to pay to the keepers of the King's leopard in the Tower of London sixpence the day for the sustenance of the leopard, and three halfpence a day for diet of the said keeper. More in the 16th of Edward III., one lion, one lioness, and one leopard, and two cat lions in the said Tower, were committed to the custody of Robert, the son of John Bowre.—Stow, p. 19.

September, 1586.—The keeping of the Lyones in the Tower graunted to Thomas Gyll and Rafe Gyll with the Fee of 12d. per diem, and 6d. for the Meat of those Lyons.—Lord Burghley's Diary in Murdin, p. 785.

A century ago the lions in the Tower were named after the reigning Kings; and it was long a vulgar belief "that when the King dies, the lion of that name dies after him." Addison alludes to this popular error in his own inimitable way:—

Our first visit was to the lions. My friend [the Tory Fox Hunter], who had a great deal of talk with their keeper, enquired very much after their health, and whether none of them had fallen sick upon the taking of Perth, and the flight of the Pretender? and hearing they were never better in their lives, I found he was extremely startled: for he had learned from his cradle that the lions in the Tower were the best judges of the title of our British Kings, and always sympathised with our Sovereigns.—Addison, The Freeholder, No. 47.

The Menagerie was removed in November 1834. The present refreshment-room, by the ticket-house, occupies the site.

The Armouries contain a very fine and valuable collection of armour and weapons. This collection was historically arranged by Sir Samuel Meyrick, and rearranged and classified by J.R. Planché in 1869. Amongst this collection are also many of the old instruments of torture, etc., but we must refer to the Official Catalogue for particulars.

Eminent Persons confined in the Tower.—Wallace; Roger Mortimer, 1324; John, King of France; Charles, Duke of Orleans, father of Louis XII.; The duke, who was taken prisoner at the battle of Agincourt, acquired a very great proficiency in our language. A volume of his English poems, preserved among the Royal MSS. in the British Museum, contains the earliest known representation of the Tower, and has often been engraved. Queen Anne Boleyn, executed May 19, 1536, by the hangman of Calais, on a scaffold erected within the walls of the Tower; Queen Katherine Howard, fourth wife of Henry VIII., beheaded on a scaffold erected within the walls of the Tower, February 14, 1541–1542; Lady Rochford was executed at the same time. Sir Thomas More, 1534; Archbishop Cranmer; Protector Somerset, 1551–1552; Lady Jane Grey, beheaded on a scaffold erected within the walls of the Tower, February 12, 1554; Sir Thomas Wyatt, beheaded on Tower Hill, April 11, 1554; Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, beheaded on a scaffold erected within the walls of the Tower, February 25, 1601.

It is said I was a prosecutor of the death of the Earl of Essex, and stood in a window over-against him when he suffered, and puffed out tobacco in disdain of him. But I take God to witness I had no hand in his blood, and was none of those that procured his death. My Lord of Essex did not see my face at the time of his death, for I had retired far off into the Armoury, where I indeed saw him, and shed tears for him, but he saw not me.—Sir Walter Raleigh's Last Speech.

Sir Walter Raleigh. He was on three different occasions a prisoner in the Tower; once in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, on account of his marriage, and twice in the reign of King James I. Here he began his History of the World; here he amused himself with his chemical experiments; and here his son, Carew Raleigh, was born. Lady Arabella Stuart, and her husband William Seymour, afterwards Duke of Somerset. Seymour escaped from the Tower.

In the meane while Mr. Seymour, with a Perruque and a Beard of blacke Hair, and in a tauny cloth suit, walked alone without suspition from his lodging out at the great Weste Doore of the Tower, following a Cart that had brought him billets. From thence he walked along by the Tower Wharf by the Warders of the South Gate, and so to the Iron Gate, where Rodney was ready with oares for to receive him.—Mr. John More to Sir Ralph Winwood, June 8, 1611 (Winwood, vol. iii. p. 280).

Sir Thomas Overbury: he was committed to the Tower on April 21, 1613, and found dead on September 14 following, having been poisoned at the instigation of the profligate Countess of Somerset. Sir John Eliot, who wrote here his Monarchy of Man; he died in the Tower, November 27, 1632. Earl of Strafford, 1641. Archbishop Laud, 1640–1543 [1641–1645]. John Selden. Lucy Barlow, the mother of the Duke of Monmouth. Cromwell discharged her from the Tower in July 1656.1 Sir William Davenant. Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham. Sir Harry Vane, the younger. Sir William Coventry.

March 11, 1668–1669.—Up and to Sir W. Coventry to the Tower.... We walked down to the Stone Walk, which is called, it seems, my Lord of Northumberland's walk, being paved by some one2 of that title who was prisoner there: and at the end of it there is a piece of iron upon the wall with his armes upon it, and holes to put in a peg for every turn they make upon that walk.—Pepys.

Earl of Shaftesbury; Earl of Salisbury, temp. Charles II. When Lord Salisbury was offered his attendants in the Tower he only asked for his cook. The King was very angry. William, Lord Russell, 1683; Algernon Sidney. 1683; Seven bishops, June 8, 1688; Lord Chancellor Jeffreys, 1688; the great Duke of Marlborough, 1692. Sir Robert Walpole, 1712 (Granville, Lord Lansdowne, the poet, was afterwards confined in the same apartment, and has left a copy of verses on the occasion.) Harley, Earl of Oxford, 1715; William Shippen, M.P. for Saltash, for saying, in the House of Commons, of a speech from the throne by George I., "that the second paragraph of the King's speech seemed rather to be calculated for the meridian of Germany than Great Britain; and that 'twas a great misfortune that the King was a stranger to our language and constitution." He is the "downright Shippen" of Pope's poems. Bishop Atterbury, 1722.

How pleasing Atterbury's softer hour,

How shone his soul unconquered in the Tower!—POPE.

At his last interview with Pope Atterbury presented Pope with a Bible. When Atterbury was in the Tower Lord Cadogan was asked, "What shall we do with the man?" His reply was, "Fling him to the lions." Dr. Freind; here he wrote his History of Medicine. Earl of Derwentwater; Earl of Nithsdale; Lord Kenmuir. Lord Nithsdale escaped from the Tower, February 28, 1715, dressed in a woman's cloak and hood, provided by his heroic wife, which were for some time after called "Nithsdales." The Earl of Derwentwater and Lord Kenmuir were executed on Tower Hill. The history of the Earl of Nithsdale's escape, contrived and effected by his countess with admirable coolness and intrepidity, is given by the countess herself, in a letter to her sister, printed in the appendix to Cromek's Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song, p. 311. Lords Kilmarnock, Balmerino, and Lovat, 1746. The block on which Lord Lovat was beheaded is preserved in the Armoury. John Wilkes, 1762; Lord George Gordon, 1780; Sir Francis Burdett, April 6, 1810. [See Piccadilly.] Arthur Thistlewood, March 3, 1820. [See Cato Street.

Persons born in. Carew Raleigh (Sir Walter Raleigh's son); Mrs. Hutchinson, the biographer of her husband; Countess of Bedford, (daughter of the infamous Countess of Somerset, and mother of William Lord Russell).

The chief officer of the Tower is the Constable, a dignity dating from the Conquest, and first held by Geoffrey de Mandeville. Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert de Burgh, Sir Thomas Fairfax, the Duke of Wellington, Sir John Fox Burgoyne, and Lord Napier of Magdala, are amongst the familiar historical characters who have held the post of Constable of the Tower. The present (1890) Constable is Field-Marshal Sir Daniel Lysons. [See St. Peter's ad Vincula.]

The entrance to the Tower is from Tower Hill by the western gate. Admission from ten to four by tickets, for the Armoury and White Tower, 6d.; and for the Crown Jewels 6d. each person; but on Mondays and Saturdays free.

1 Harl. MS., 6859, p. 27; MS. dated 1680.

2 Whitelocke, ed. 1732, p. 106.

3 Ibid., p. 418.

1 Archaeological Journal, vol. i. p. 289.

1 Whitlocke, p. 649.

2 Henry, ninth Earl.