New Bethlehem Hospital

Names

- Bethlehem Hospital

- Bedlam

- New Bethlem

- New Bethlehem Hospital

- Bedlem

Street/Area/District

- London Wall

Maps & Views

- 1677 A Large and Accurate Map of the City of London (Ogilby & Morgan): New Bethlehem

- 1720 London (Strype): Bethlehem Hospital

- 1736 London (Moll & Bowles): New Bethlem

- 1746 London, Westminster & Southwark (Rocque): Bethlehem Hospital

- 1761 London (Dodsley): Bethlem Hospital

Descriptions

from A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, by John Strype (1720)

Bethlehem Hospital

[The] greatest Ornament [of the street called London Wall] is Sion College, already treated of; and New Bethlem, seated on the other side of London Wall, in Moorfields.

… On the South side [of Coleman Street Ward without the City Walls] is Bedlem or Bedlam, for the Lunaticks.

This Hospital of Bethlem, or Bedlam, is pleasantly seated, with its Front regarding Moorfields. It is a very long Building, extending it self almost the breadth of the Field. It is stately and graceful to behold, and tends much to the Honour of the City: The Charge of which Building cost about 17000l. It is inclosed with a Wall, and hath an Iron Gate for entrance, in the middle, with a fine Free stone Pavement, for a Walk, from one end to the other; and at each end, a large Place for those that are coming to their Senses, to walk and air themselves in. This Hospital is made very convenient within, for such a purpose, to keep Lunaticks in; having four Wards or long Rooms, as now severed in the middle, for the keeping apart the Men from the Women. Of these Wards, two are for the Men, and two for the Women, the one over the other. And on one of the sides of the Rooms or Wards, are small Rooms, in which they are kept, when not fit to walk in the Ward. But of this Hospital, see more in Book I. Chap. XXVI. (64)

Bethlem Hospital; commonly called Bedlam.

The [original] Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlem, seated in Bishopsgate Ward, without the City Wall, betwixt Bishopsgate-street and Moorfields; first founded by Simon Fitz Mary, one of the Sheriffs of London, in the Year of our Lord 1246, to be a Priory of Canons with Brethren and Sisters, and to wear a Star upon their Copes and Mantles; and to receive the Bishop of Bethlehem, and the Canons or Messengers of the Church of Bethlehem, whensoever they should have occasion to travel hither; as will appear more at large in the said Fitz Maries Charter, exemplified in its proper Place in Bishopsgate Ward.

First Founded for a Priory of Canons with Brethren and Sisters. R.B.

K. Henry VIII. gave this House to the City of London. They converted it to a House or Hospital for the Cure of Lunaticks: But not without Charges at so much the Week, for these brought in, if they or their Relations were of Ability; and if not, then at the Parish Charge, in which they were Inhabitants.

This Hospital stood in an obscure and close Place, near unto many common Sewers; and also was too little to receive and entertain the great Number of distracted Persons, both Men and Women. Therefore upon a charitable Consideration of the same, the Lord Maior, Aldermen, and Common Council of the City of London, did grant unto the Governors a sufficient Piece of Ground against London Wall on the Southside of the Lower Quarters of Moorfields. And in pursuance thereof they did proceed to build a new Hospital, which now shews a stately and magnificent Structure, containing in length from East to West 540 Foot, and in Breadth 40 Foot, besides the Wall which incloseth the Gardens before it, which is neatly ordered with Walks of Free Stone round about, and Grass Plats in the Middle. And besides this Garden, there is at each end another for the Lunatick People, when they are a little well of their Distemper, to walk in for their Refreshment; this Wall is in Length 680 Foot, and in Breadth 70 Foot at each end, being very high; and that part fronting the Fields hath Iron Grates in several Places of the Wall, to the end that Passengers, as they walk in the Fields, may look into the Garden.

…

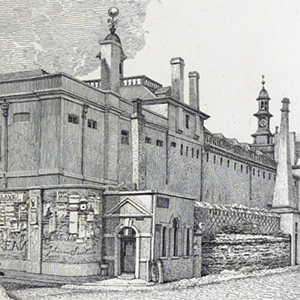

New Bethlem seated in Moorfields. This large Fabrick is built of Brick and Free Stone; the Gate or Entrance all of Stone, with two Figures of a distracted Man and Woman in Chains (a curious Piece of Sculpture) over the Gate. And in this, as well as in the Building, the Architecture is good. It hath a large Cupolo with a gilded Ball, and a Vane at the Top of it, and a Clock within, and three fair Dials without.

…

The great Benefit that doth accrue hence to the City of London, and other Parts of this Kingdom, is very considerable, if we consider the great Number of distracted Persons brought in Yearly, and most receiving Cure, and being for the most part Poor and Indigent.

But to give yet a further and more particular Account of the present State of this noble and useful Foundation, the late learned Physician to the same, Dr. Edward Tyson, was, upon my Solicitation, pleased to draw up this brief Relation following:

The Hospital of Old Bethlehem being ruinous, and too strait and close for the Patients; in the year 1675, the Lord Maior, Aldermen, Governors, and Citizens of London, began to build this new Hospital in Moorfields, nigh the Wall of the City: And though the Structure be so large and magnificent, yet by the great Application that was made in hastning the Building, 'twas finished the next Year, as appears by an Inscription over the Arch facing the Entrance into the said Hospital, viz.

This Hospital was begun to be built in April, 1675, and was finished in July, 1676.

Sir William Turner, Knt. and Alderman, President.

Benjamin Ducane, Esq; Treasurer.

The Charge of this Building was computed to amount to nigh 17000l. where now (with some Additions lately made) there is an Accommodation for 150 Patients, whereas in the old there were usually but 50 or 60.

The inside consists chiefly of Two Galleries, over the other, each 193 Yards long, 13 Foot high, and 16 Foot broad; not including the Cells for the Patients, which are 12 Foot deep. The said Galleries are divided in the Middle by two Iron Grates. So that now all the Men are placed in one End of the House, and all the Women at the other, each having their proper Conveniences; as likewise a Stove Room, where in the Winter they have a Fire to warm them; and at each End of the lower Gallery a large Grass Plot, to air and refresh themselves in the Summer: And in each Gallery Servants lye, to be ready at hand on all Occasions.

Besides, below Stairs there is made of late a Bathing Place for the Patients; so contrived, as to be an hot or cold Bath, as occasion requires.

In the middle of the Upper Gallery is a large spatious Room where the Governors, and in the Lower a lesser, where the weekly Committee meet, and the Physician prescribes for the Patients.

Besides, convenient Apartments for the Steward of the House, for the Porter, Matron, Nurse, and Servants; and below Stairs, all necessary Offices for keeping and dressing the Provisions, for washing, and other Necessaries belonging to so large a Family.

The Hospitals of Bridewell and Bethlem being made one Corporation, they have the same President, Treasurer, Governors, Clerk, Physician, Surgeon, Apothecary: But each Hospital has its proper Steward and inferior Officers; and out of the Governors a particular Committee is appointed for each.

Out of the Committee appointed for Bethlem, there are six to meet weekly, who on Saturday examine the Steward's Account of Expences for the Week preceding; and after it is approved, they sign it: They are likewise to view the Provisions, the Patients that are to be received or discharged; and direct other Matters belonging to the said Hospital.

In the Passage just within the Hospital are hung up these Orders. (192–193)

from London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions, by Henry Benjamin Wheatley and Peter Cunningham (1891)

[Bethlehem Hospital (vulg. Bedlam)], a hospital for insane people, founded in Bishopsgate Without, and for a different purpose, in 1246, by Simon Fitz-Mary, one of the Sheriffs of London. "He founded it to have been 'a priory of canons with brethren and sisters."2 The site of the original hospital was that known long after its removal as Old Bethlemen, subsequently as Liverpool Street. The greater part of it is now occupied by the stations of the North London and Great Eastern Railways. On the petition of Sir John Gresham, Lord Mayor, Henry VIII. gave the building of the dissolved priory, in 1547, to the City of London, in order that it might be converted into a hospital for lunatics. In 1557 the management was given to the governors of Bridewell Hospital. [See Bridewell.]

Then had ye [at Charing Cross] one house, wherein sometime were distraught and lunatic people, of what antiquity founded or by whom I have not read, neither of the suppression; but it was said that sometime a king of England, not liking such a kind of people to remain so near his palace, caused them to be removed farther off, to Bethlem without Bishopsgate of London, and to that hospital the said house by Charing Cross doth yet remain.—Stow, p. 167.

By the beginning of the 17th century Bethlehem Hospital had become one of the London sights, and it so continued till the last quarter of the 18th century. In Webster's Westward Ho! (410, 1607), some of the characters, to pass the time while their horses are being saddled at "the Dolphin, Without Bishopsgate," resolve to "cross over" the road "to Bedlam, to see what Greeks are within," and a highly comic scene ensues. One of the party happening to turn his back the rest persuade the keeper that their friend is a lunatic, that his "pericranium is perished."

Greenshield. Look you, Sir, here's a crown to provide his supper. He's a gentleman of a very good house: you shall be paid well if you convert [i.e. cure] him. To-morrow morning bedding and a gown shall be sent in, and wood and coal.

Keeper. Nay, Sir, he must ha' no fires.

Greens. Let his straw be fresh and sweet, we beseech you, Sir.

Westward Ho! Act iv. sc. 3.

Ben Jonson in his Silent Woman makes it a part of Lady Haughty's instructions to her friend for taming a husband to make him attend her to the sights of London. "And go with us to Bedlam, to the China houses, and to the Exchange."1 The same combination occurs in the Alchemist, which comedy supplies another local touch:—

It may be,

For some good penance you may have it yet; A hundred pounds to the box at Bethlem.—Alchemist, Act iv. Sc. 3.

The Deputy Feodary of Somersetshire reported to Cecil, November 10, 1609, that he had found a lunatic in an under room chained and ironed on a straw bed "After the fashion of Bedlam."2

There seem to have been many complaints of the management. In May 1619 Dr. Hilkiah Crooke petitioned the King, James I., to "urge the Commissioners to be diligent in the prosecution of the commission, and to provide separate government for the hospital which had not thriven this hundred years."3 A little later (1632) we learn for the first time what was the accommodation provided for the patients. Besides parlour, kitchen and larders below stairs, there were "twenty-one rooms wherein the poor distracted people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more for servants and the poor to lie in, and a long waste room now being contrived and in work, to make eight more rooms for poor people to lodge where they lacked room before." With some additions recently made there does not seem to have been provision made for more than sixty patients. The Great Fire did not reach Bethlehem Hospital, but shortly afterwards, when building was going on all around and many alterations were being made in the streets, it was decided rather than attempt to repair the buildings, which had become very dilapidated and quite inadequate to their purpose, to erect a larger hospital in Moorfields somewhat farther from the heart of the city. Simon Fitz-Mary's Hospital was accordingly taken down, as soon as the new building was ready for the reception of the patients. An inscription over the entrance stated that it was commenced in April 1675 and finished in July 1676, an instance of rapid building for those times. Robert Hooke was the architect, "the cost was nigh £17,000." In this as in other cases quick building did not imply sound building. When it was pulled down in 1814 it was discovered that the foundations were very bad, "it having been built on a part of the Town-ditch, and on a soil very unfit for the erection of so large a building." According to its historian,1 whose knowledge of Paris must have been very vague, "the design was taken from the Chateau de Tuilleries at Versailles. Louis XIV., it is said, was so much offended that his palace should be made a model for a hospital, that in revenge he ordered a plan of St. James's to be taken for offices of a very inferior nature." Had this story had any foundation it would certainly have been alluded to by M. Misson, who, as a French refugee, bore no love to Louis XIV. He contents himself with saying (1697) that it is "well situated, and has in front several spacious and agreeable walks," slily adding, "all the mad folks of London are not in this hospital."2 Evelyn expressed the general admiration of the new building. Like its predecessor it was open as an exhibition to the public, and became a common promenade like the middle aisle of old St. Paul's, or the gravel walks of Gray's Inn. At one time the hospital "derived a revenue of at least £400 a year from the indiscriminate admission of visitants." In 1770 it appeared at last to have dawned on the authorities that the practice "tended to disturb the tranquillity of the patients."3 The practice was continued for a few years longer—Johnson with the faithful Boswell visited it, as we shall see, in 1775 when it was put an end to and no one was afterwards admitted without a particular introduction.

April 21, 1657.—Waited on my Lord Hatton, with whom I dined; at my return I stept into Bedlam, where I saw several poor miserable creatures in chains; one of them was mad with making verses.—Evelyn.

Rule V.—That no person do give the lunatics strong drink, wine, tobacco, or spirits: Nor be permitted to sell any such thing in the hospital.

Rule VI.—That such of the lunatics as are fit be permitted to walk in the yard till dinner time and then be locked up in their cells; and that no lunatic that lies naked, or is in a course of physic, be seen by anybody without order of the physician.—Rules drawn up in 1677 (Strype's Stow).

April 18, 1678.—I went to see new Bedlam Hospital, magnificently built and most sweetly placed in Morefields, since the dreadful fire in London.—Evelyn.

Ned Ward, in The London Spy, 1699, describes in his coarse way visits to Bedlam, and the behaviour of the inmates. So also, some ten years later, does Steele in The Tatler. Jordan composed a song "in commendation of the founders of New Bethlehem," in which he alluded to the large number of applicants for admission:—

Could they their building run

From thence to Islington,

'Twould never hold 'em.

Fairholt's Lord Mayor's Pageants, p. 87.

On Tuesday last I took three lads, who are under my guardianship, a rambling, in a hackney-coach, to show them the Town; as the Lions, the Tombs, Bedlam, and the other places, which are entertainments to raw minds, because they strike forcibly on the fancy.—Tatler, No. 30, June 18, 1709.

If we consult the collegiates of Moorfields, we shall find that most of them are beholden to their pride for their introduction into that magnificent palace. I had the curiosity to enquire into the particular circumstances of these whimsical freeholders, and learned from their own mouths the condition and character of each of them.... There were at that time five duchesses, three earls, two heathen gods, an emperor, a prophet.... A leather seller of Taunton whispered me in the ear that he was the Duke of Monmouth, but begged me not to betray him. At a little distance from him sat a tailor's wife, who asked me as I went by if I had seen the sword-bearer? Upon which I presumed to ask her who she was? and was answered, "My Lady Mayoress."—Tatler, No. 127, January 28, 1710.

To gratify the curiosity of a country friend I accompanied him a few weeks ago to Bedlam. It was in the Easter week, when, to my great surprise, I found a hundred people at least, who, having paid their twopence apiece, were suffered, unattended, to run rioting up and down the wards, making sport and diversion of the miserable inhabitants, etc.—The World, No. 23, June 7, 1753.

On Monday, May 8 [1775] we went together and visited the mansions of Bedlam. I had been informed that he [Johnson] had once been there before with Mr. Wedderburne (now Lord Loughborough), Mr. Murphy, and Mr. Foote; and I had heard Foote give a very entertaining account of Johnson's happening to have his attention arrested by a man who was very furious, and who, while beating his straw, supposed it was William, Duke of Cumberland, whom he was punishing for his cruelties in Scotland in 1746.—Boswell, by Croker, p. 445.1

In those days when Bedlam was open to the cruel curiosity of holiday ramblers I have been a visitor there. Though a boy, I was not altogether insensible to the misery of the poor captives, nor destitute of feeling for them. But the madness of some of them had such a humorous air, and displayed itself in so many whimsical freaks, that it was impossible not to be entertained at the same time that I was angry with myself for being so.—Cowper to Rev. John Newton, July 19, 1784; Southey's Cowper, vol. v. p. 63.

The first hospital could accommodate only 50 or 60 patients, and the second 150, the number there in Strype's time. By the end of the 18th century the hospital had become quite inadequate to the increased requirements. The City offered to grant a lease of some adjoining ground for its enlargement, but a committee, appointed to consider what steps should be taken reported, April 1799, that the whole building was "dreary, low, and melancholy," and the interior ill contrived, and further that it was in a very dilapidated condition. Eventually it was determined to remove the hospital to a more open situation, and the Bridge House Committee agreed to exchange a site of nearly 12 acres in St. George's Fields, Lambeth, for the 2 acres on which the hospital stood. An Act of Parliament was passed in 1810 sanctioning the exchange and removal. …

Celebrated Persons confined in.—Oliver Cromwell's tall porter.

The renowned Porter of Oliver Cromwell had not more volumes around his cell in the College of Bedlam, than Orlando in his present apartment.—Tatler, No. 51.

Nat Lee, the dramatic poet. He was here for four years; the Duke of York, afterwards James II., paying for the cost of his confinement.

I remember poor Nat Lee, who was then upon the verge of madness, yet made a sober and a witty answer to a bad poet who told him "It was an easie thing to write like a madman." "No," said he, "it is very difficult to write like a madman, but it is a very easy matter to write like a fool."—Dryden to Dennis (Malone, vol. ii. p. 35).

Richard Stafford, whose curious history Mr. Cunningham discovered in the Letter Book of the Lord Steward's Office. He was sent to Bethlehem Hospital by an order of the Board of Green Cloth, November 4, 1691; his particular offence being that

he had been very troublesome to their Mats Court at Kensington, and had dispersed many Scandalous Pamphlets and libells filled wth Enthusiasm and Sedition.

A second order was sent, November 11, directing that on account of the

many persons who do frequently resort to him, by whose means he may proceed in his former evill practices, and be encouraged to write and publish more of his treasonable Books and Papers ... he may not be permitted to have either papers, pen, or ink; unlesse upon some especiall occasion of writeing either to his Father, or some other near Friend, the said Letter being also perused either by yourselves or by some trusty person whom you can much confide in, and that some person may be by to see that he doth not write more than is thus allowed him.

Again, on April 11 of the following year, the Board having

received Information that a great concourse of people do daily resort to Richard Stafford, to whom he doth preach and scandalously reflect on ye government and by whose means pen, ink, and paper being conveyed to him, he doth still continue to write Pamphletts and Libells more full of Treason and Sedition, then those for which we sent him to yor hospitall, some of ye said persons do gett ye said Libells printed, and he doth disperse them through ye Window of his Roome into ye Streete, desire that he may be more closely confined where he may not have that conveniency to disperse his Libells, and that no person be suffered to speak to him but in ye presence of a keeper, nor any suspected person suffered to come to him.

Hannah Snell (d. 1792). She was an out-pensioner of Chelsea Hospital, on account of the wounds she received at the siege of Pondicherry.1 Peg Nicholson, for attempting to stab George III.

When Mayors by dozens at the tale affrighted,

Got drunk, addressed, got laughed at, and got knighted.

ROLLIAD.

She died here, May 17, 1828, after a confinement of 42 years. Hadfield, for attempting to shoot the same king in Drury Lane Theatre. Oxford, for firing at the Queen in St. James's Park. M'Naghten, for shooting Mr. Edward Drummond at Charing Cross. He mistook Mr. Drummond, the private secretary of Sir Robert Peel, for Sir Robert Peel himself. Jonathan Martin, who set fire to York Minster in 1829, died here in 1838.

At first the funds of the hospital proving insufficient for the number of lunatics requiring admission, the Governors, in order to relieve the establishment, admitted out-door patients or pensioners, who bore upon their arms the license of the hospital.

Till the breaking out of the Civil Wars, Tom o' Bedlam did travel about the country; they had been poor distracted men, but had been put into Bedlam, where, recovering some soberness, they were licentiated to go a-begging, i.e. they had on their left arm an armilla of tinn, about four inches long; they could not get it off; they wore about their necks a great horn of an ox in a string or bawdry, which when they came to an house for alms, they did wind, and they did put the drink given them into this horn, whereto they did put a stopple. Since the wars I do not remember to have seen any one of them.—Aubrey, Nat. Hist, of Wiltshire, p. 93.

"Poor Tom, thy horn is dry!" is Edgar's exclamation (in Lear) in his assumed character of a Tom o' Bedlam. If, as Aubrey supposes, these out-door Tom o' Bedlams ceased to exist after the Civil War, "sham Toms" traded on the public charity many years later. The following advertisement was issued by the Governors of the hospital in June 1675:—

Whereas several vagrant persons do wander about the City of London and Countries, pretending themselves to be lunaticks, under cure in the Hospital of Bethlem commonly called Bedlam, with brass plates about their arms, and inscriptions thereon. These are to give notice that there is no such liberty given to any patients kept in the said Hospital for their cure, neither is any such plate as a distinction or mark put upon any lunatick during their time being there, or when discharged thence. And that the same is a false pretence to colour their wandering and begging, and to deceive the people to the dishonour of the Government of that Hospital.—London Gazette, No. 1000.

Hatton, describing Bethlehem in 1708, says, "When these people are cured of their malady, there are no tickets given them, as I have seen on the wrists of some, who I am assured are all shams."

Bishop Warburton, writing to Hurd,1 says, "I begin to think with Bolingbroke, this earth may be the Bedlam of the universe."

I remember in the late public entry of the Preston gentlemen from their northern expedition, the late Earl of Derwentwater, when he found they were past by the Exchange, asked where they were to go to. And when they answered him they were to go to the Tower, he returned, "I think they ought to carry us to Bedlam rather than to the Tower."—Applebee's Journal, November 24, 1722.

In the vestibule of the Hospital, until their removal to the South Kensington Museum a few years back, stood the two statues of Madness and Melancholy from the outer gates of Bethlehem in Moorfields, cut by Caius Gabriel Cibber, the father of Colley.

Where o'er the gates, by his fam'd father's hand,

Great Cibber's brazen brainless brothers stand.

Pope, The Dunciad.

Brazen they are not, but formed of Portland stone, painted over. They were restored in 1814 by the younger Bacon. One is said to represent Oliver Cromwell's porter, then in Bedlam.

2 Stow, p. 62.

1 Silent Woman, Act iv. sc. 2.

2 Cal. State Papers, 1623–25, p. 542.

3 Cal. Staff Pap., James I., 1619–1623, p. 50.

1 Historical Account of the Origin, Progress, and Present State of Bethlehem Hospital, 4to, 1783.

2 Travels in England, 1719.

3 Historical Account, p. 11.

1 See also Plate 8 of The Rake's Progress, (1735), which represents a scene in Bedlam with maniacal grandeur, but exhibits two fine ladies visiting the deplorable scenes referred to in the above extracts.

1 As I went over Westminster Bridge last week, I saw we were building a new madhouse, twice as big as old Bethlehem Hospital; and surely no building would be so wanted for Englishmen.—Mrs. Piozzi to Dr. Whalley, August 13, 1815.

1 Lysons, vol. ii. p. 62.

1 Warburton's Letters, p. 299, November 2, 1759.

from A Topographical Dictionary of London and Its Environs, by James Elmes (1831)

Bethlem Hospital … in ancient times stood on the spot now called Old Bethlem, in Bishopsgate-street. The original building was formerly a priory founded in the year 1247, by Simon Fitzroy, of London, or, according to Stow, Simon Fitz-Mary, Sheriff of London in the year 1247, the thirty-first year of Henry III., on the east side of the Moor, near Finsbury, from which it was divided by a large and deep ditch. This priory he endowed by deed of gift, with lands not far from it, on which the street now called Old Bethlem stands. A copy of this deed may be found in the second volume of Maitland's History of London, Page 796. H received from Edward III., in the fourteenth year of his reign, the grant of his licence, and protection for the brethren "Militiae beatae Mariae de Bethlem," within the City of London. They were of the order of Bethlehem, or the Star, and were distinguished by a star upon their mantles. They were subject to the visitation of the Bishop of Bethlehem, who was to be entertained with his suite whenever he came to London. It does not appear whether the society was ever very numerous, but Camden says, in his third volume (Gough's Edition), page 22, that in the year 1403, it was reduced to the master only. At the suppression of monasteries by Henry VIII., Sir John Gresham, Lord Mayor of London, petitioned for it with success; for in 1547 the king granted its lands and revenues to the corporation of London, for the reception and maintenance of lunatics. In 1549 he followed it up by granting letters patent to John Whitehead, proctor of the hospital, to solicit and receive donations within the counties of Lincoln and Cambridge, the city of London and the Isle of Ely; and at a court of aldermen in the reign of Edward VI. it was ordered, that the precinct of Bethlem should be thenceforth united to the parish of St. Botolph without Bishopsgate. The number of its unfortunate patients having increased, and the ancient buildings of the priory having become much dilapidated, it was found necessary to remove it to a more spacious site, and to enlarge its accommodations. This necessary work was began in April 1644, and the corporation of London allotted a large piece of ground on the south side of Moorfields, on the north side of London-wall, for this purpose. The building was began and completed by voluntary contributions in 1676, at an expense of £17,000. The design is said to have been copied from the palace of the Tuilleries at Paris, and that Louis XIV., was so much offended by it, that he ordered a copy of our king's palace of St. James's to be taken for offices of a very humble kind. In 1708 Queen Anne granted the corporation a license to purchase and hold in fee, or for lives, or years, or otherwise, in trust for this hospital, any lands, &c. to the value of £2,000 a year. The increase of application, as there was no limitation, from all parts of the kingdom, rendered a farther enlargement necessary, therefore in 1733 two wings were added, which enabled the governors to maintain one hundred incurable patients. When these buildings were finished, the length of the hospital was 540 feet, and its breadth 40 feet. This hospital being united by the charter of Edward VI. to that of Bridewell, as mentioned in the account of St. Bartholomew's Hospital, is conducted by the same governors, being members of the corporation, and others who become so by benefactions, as will be more particularly stated in the account of Bridewell, which see. The management is confided to a committee of forty-two governors, seven of whom, with the treasurer, physician, and other officers, attend every Saturday in monthly rotation for the admission of patients and other business of the hospital; and these meetings are open for the attendance of any other governor. By the agreement and act of parliament of 1782, alluded to in the account of St. Bartholomew's Hospital, the style of this hospital was settled to be "The Mayor, Commonalty and Citizens of London, as Masters, Guardians and Governors of the House and Hospital called Bethlem, situate without and near to Bishopsgate, of the said City of London." This style is of course altered, so far as concerns its situation. The antiquity and consequent decay of the old building in Moorfields, rendered an expensive repair, or total re-building necessary. The corporation, after due deliberation, finally determined to build a new hospital in a more proper situation; and as the leases of the Bridge-house estate in St. George's-fields and Lambeth-marsh fell in at Lady-day 1810, the governors agreed with the Bridge-house committee for a ground plot of nearly twelve acres, fronting the high road leading from Newington to Westminster-bridge, on part of which were the house and gardens of the notoriously infamous Dog and Duck. … In the great hall under the portico are preserved the two celebrated statues of raving and melancholy madness, by Caius Cibber, that were formerly on the gate piers of the … hospital in Moorfields.

from the Grub Street Project, by Allison Muri (2006-present)

Bethlehem Hospital, London Wall. See also Old Bethlehem Hospital and Bethlehem Royal Hospital.